Abstract

In this artistic research I take the approach that digital works can be utilised for imagining and playing with yet impossible realities, for asking questions, and for portraying aspects of life such that we can explore these from a distance. This dissertation consists of three browser-based artworks programmed by myself in HTML, Javascript and CSS. These art experiences unfold on the screen, asking the person to interact with them in order to complete their meanings. The works incorporate, among other things, voice interaction through synthetic speech and speech input, the uses of which form an essential component of the works meanings. Each work is concerned with very different types of questions around migration, but overall, and as a triptych, the works explore what the movement brought about by migration implies from a human standpoint.

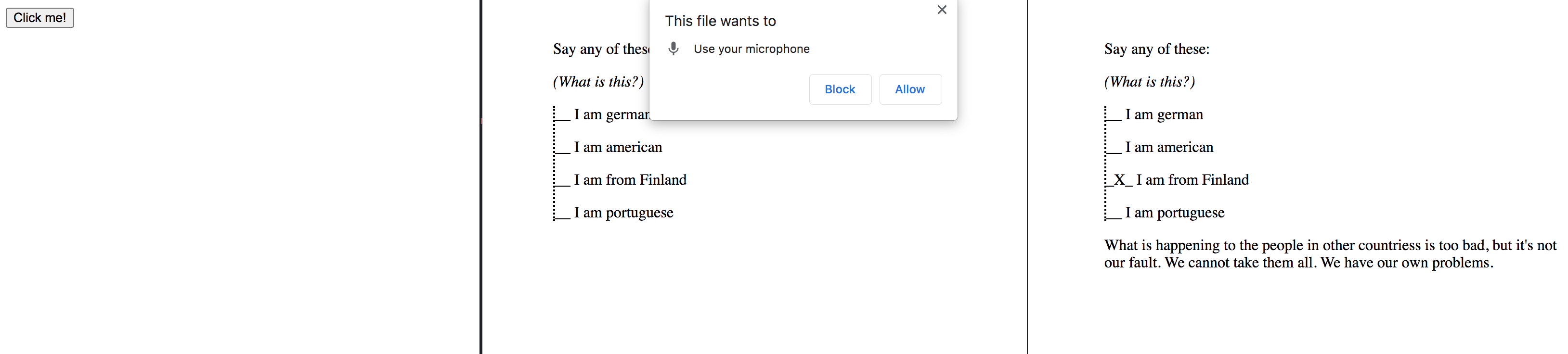

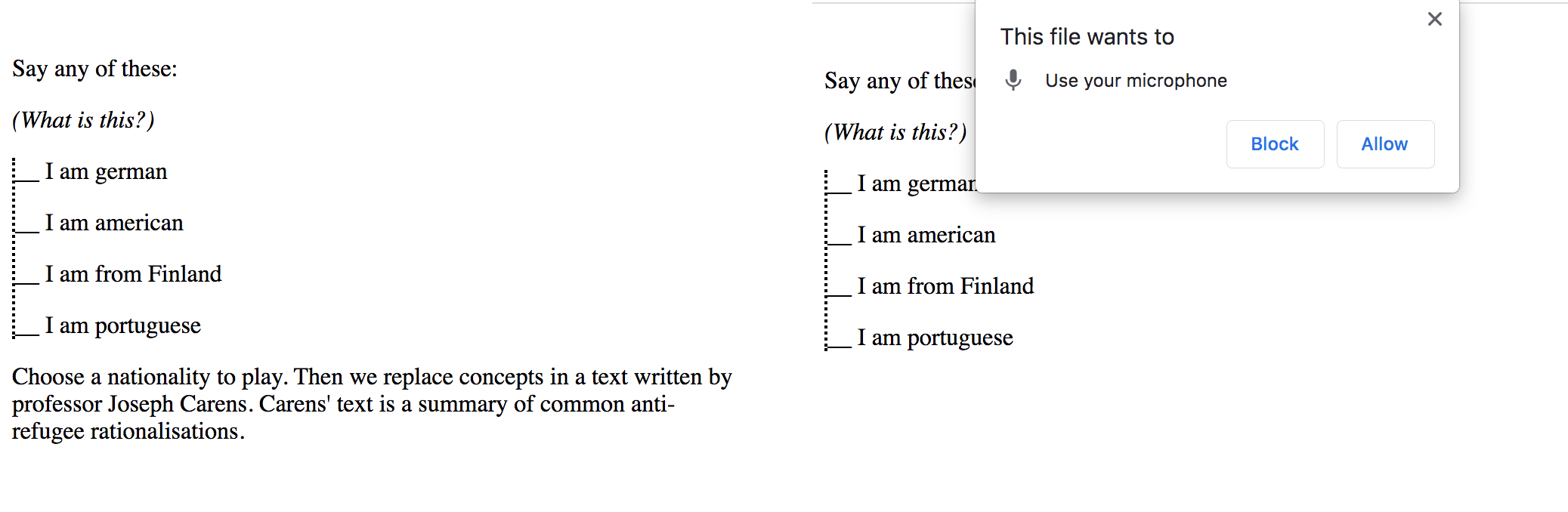

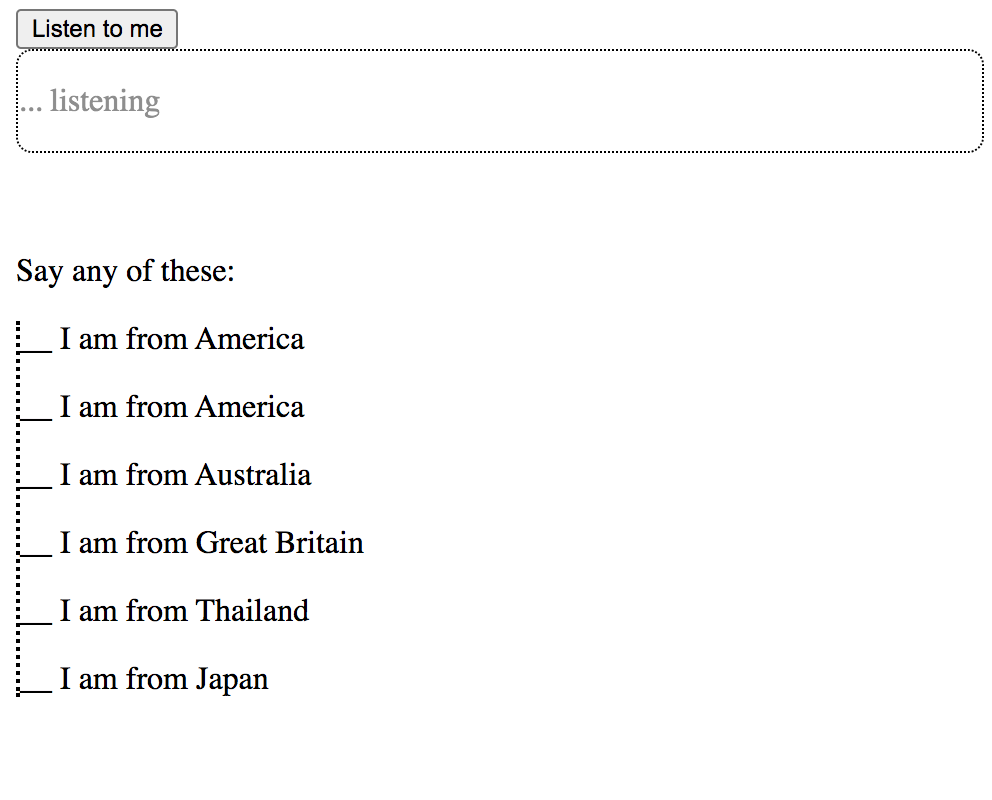

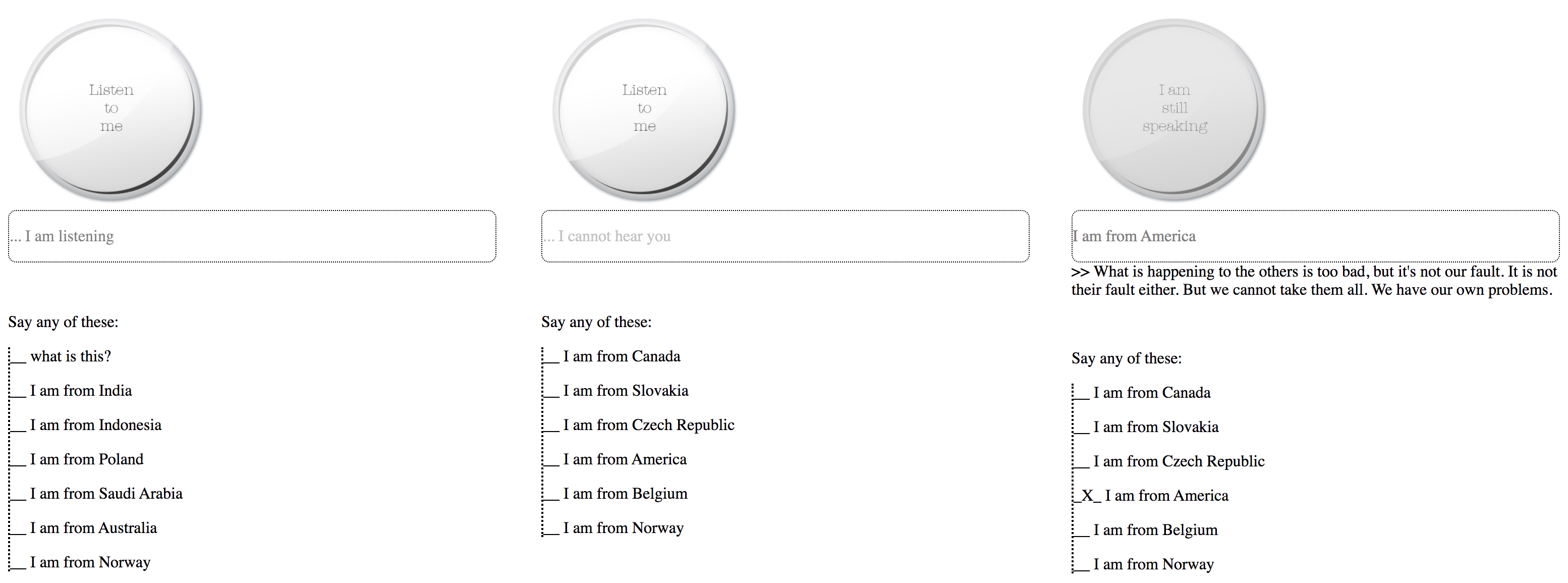

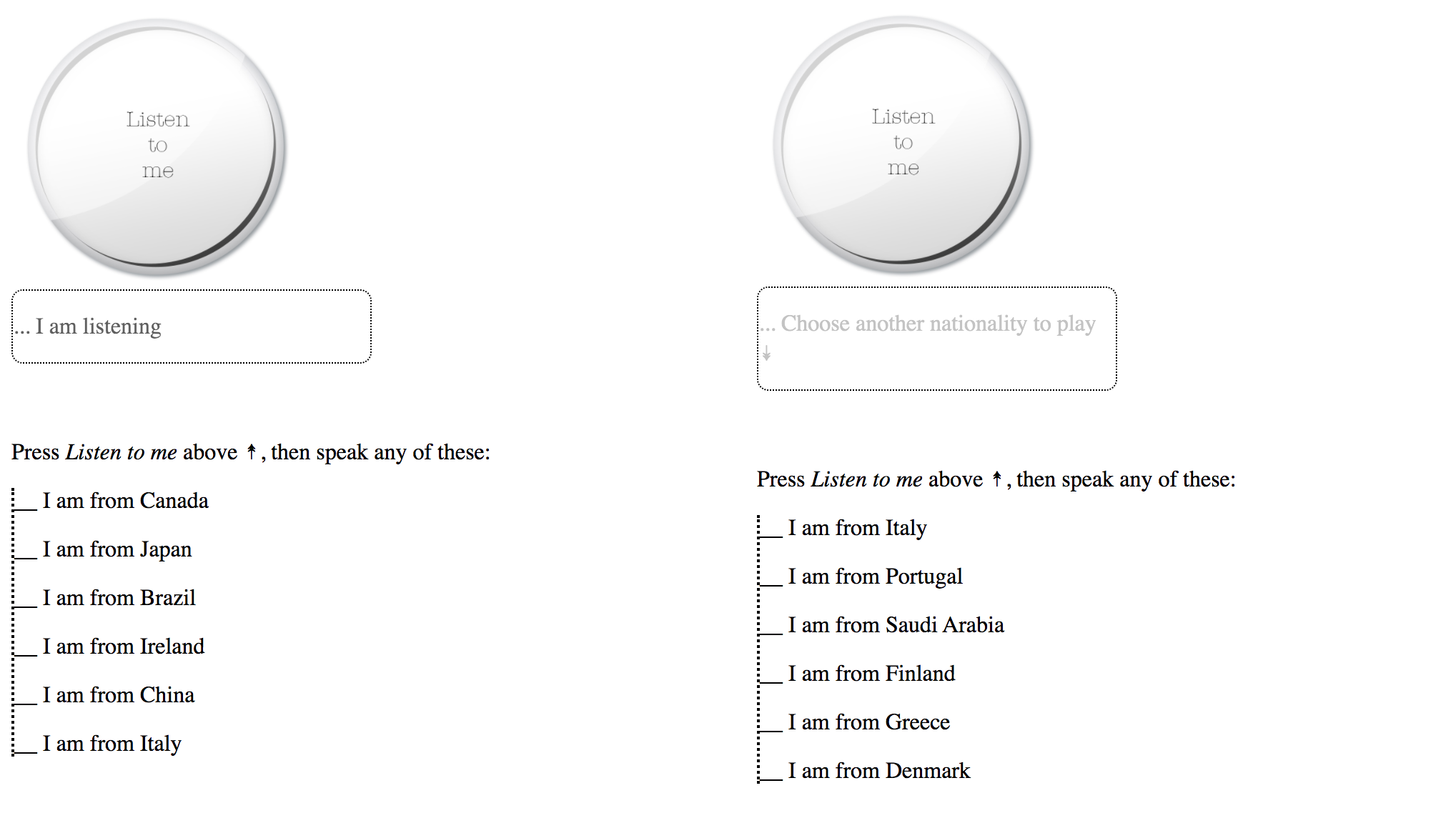

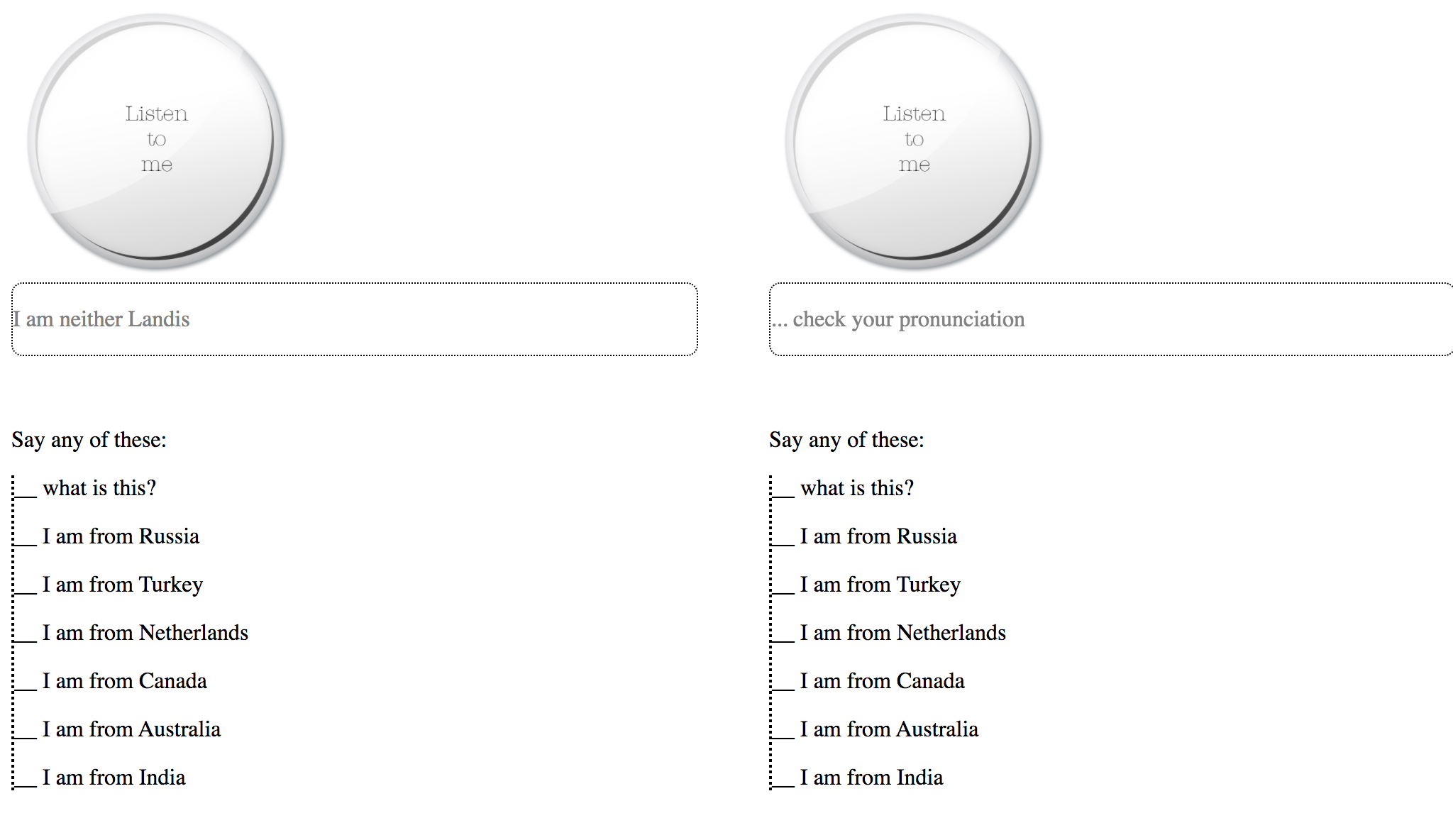

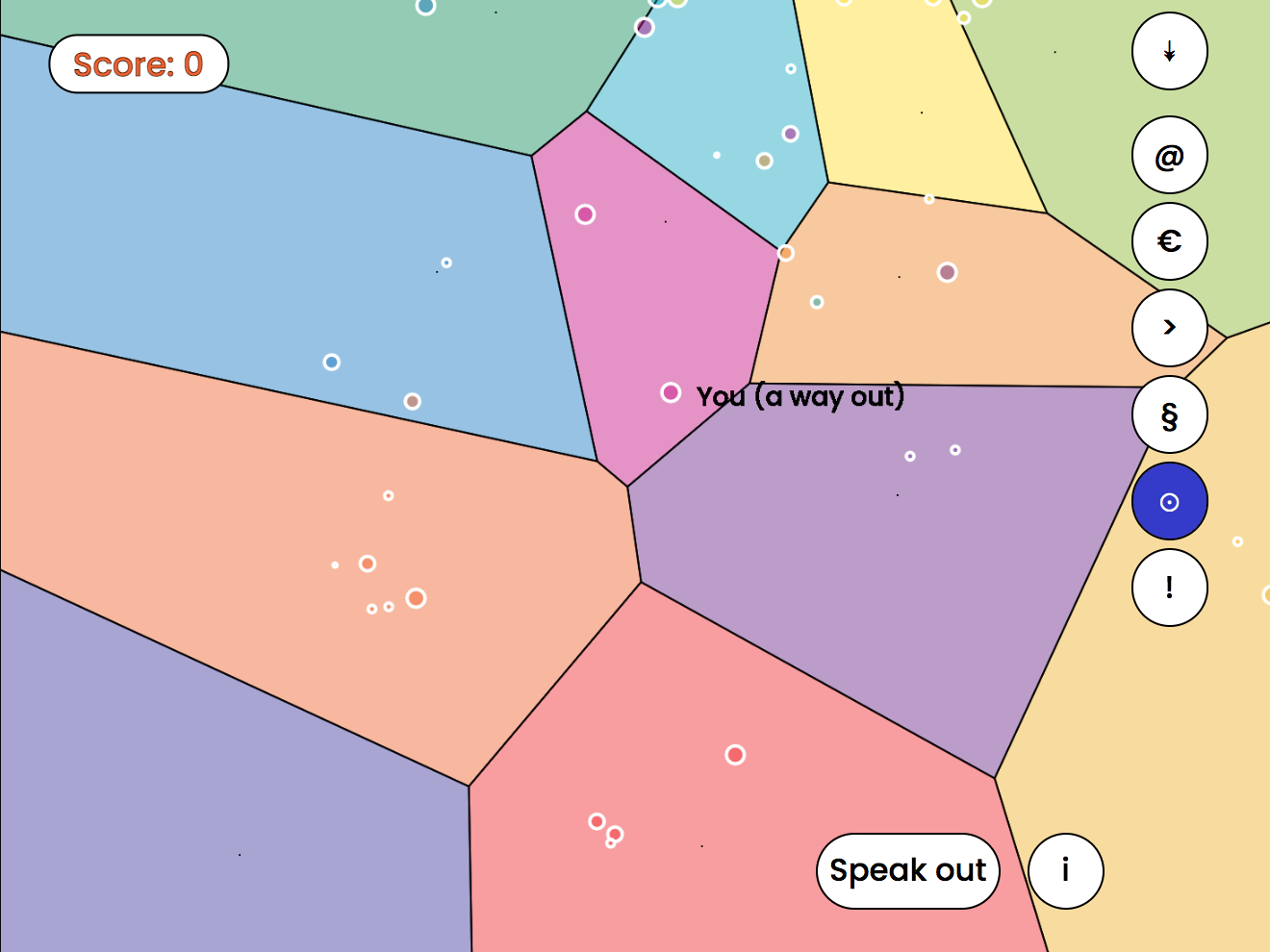

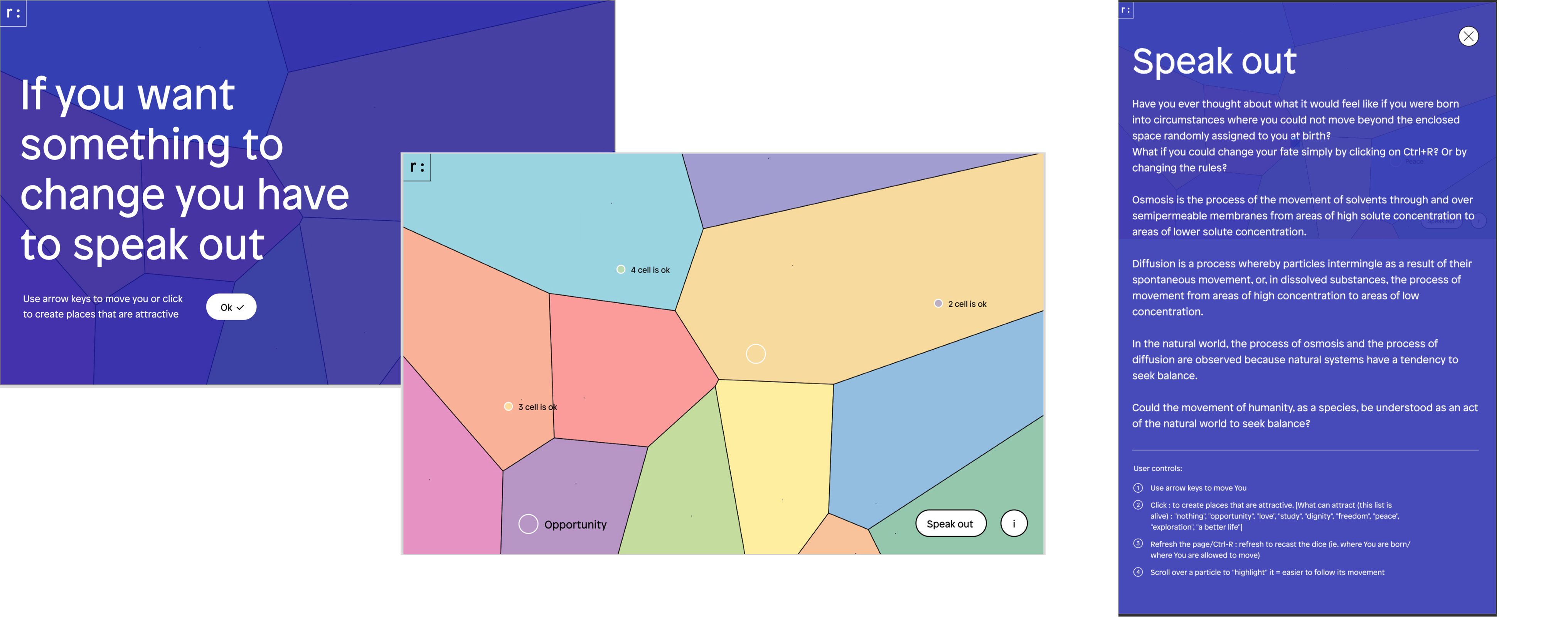

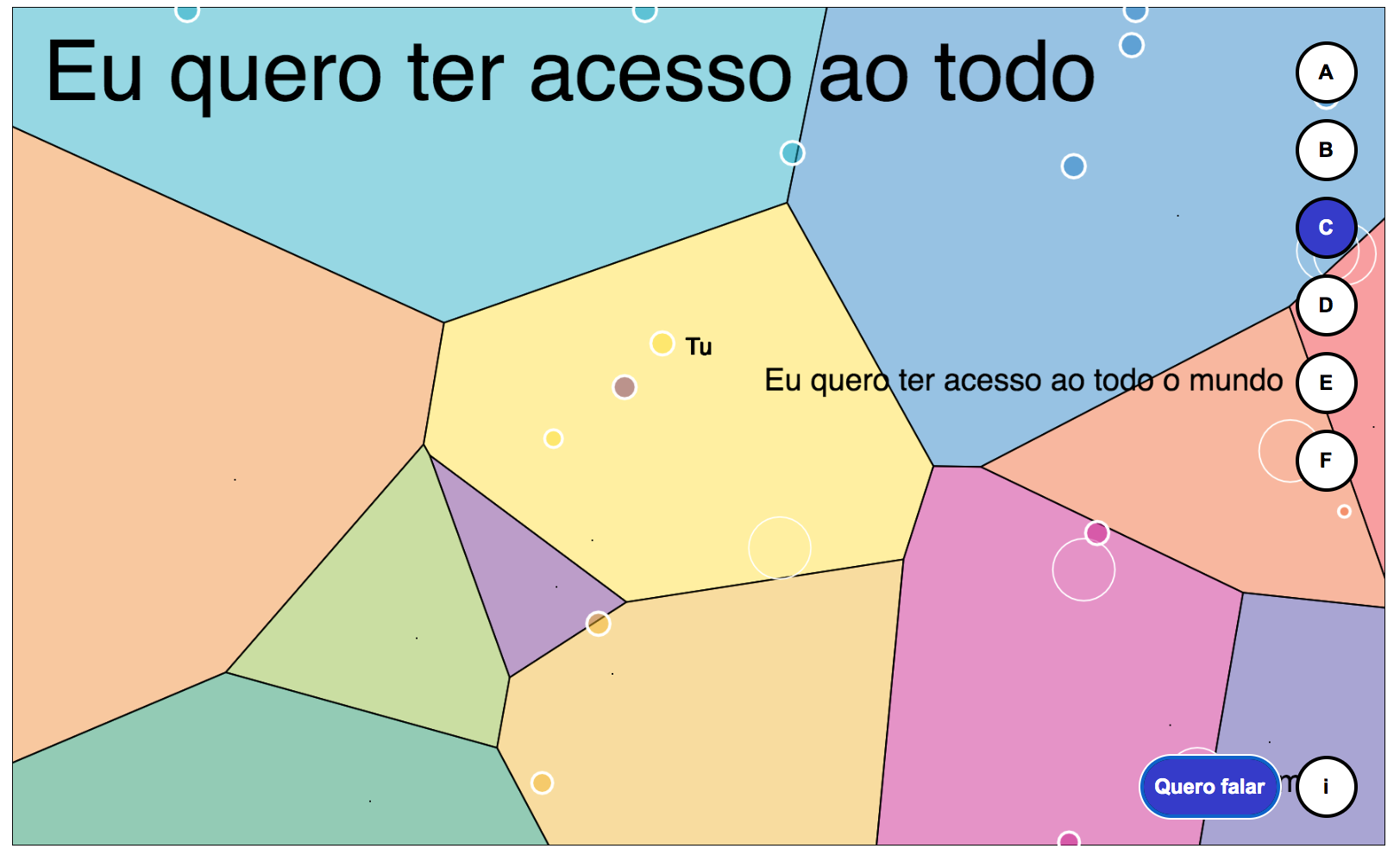

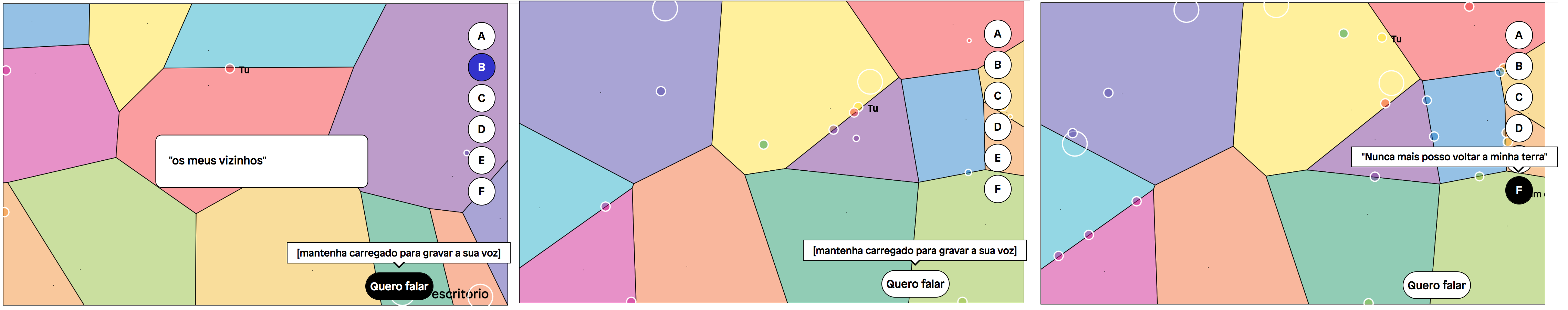

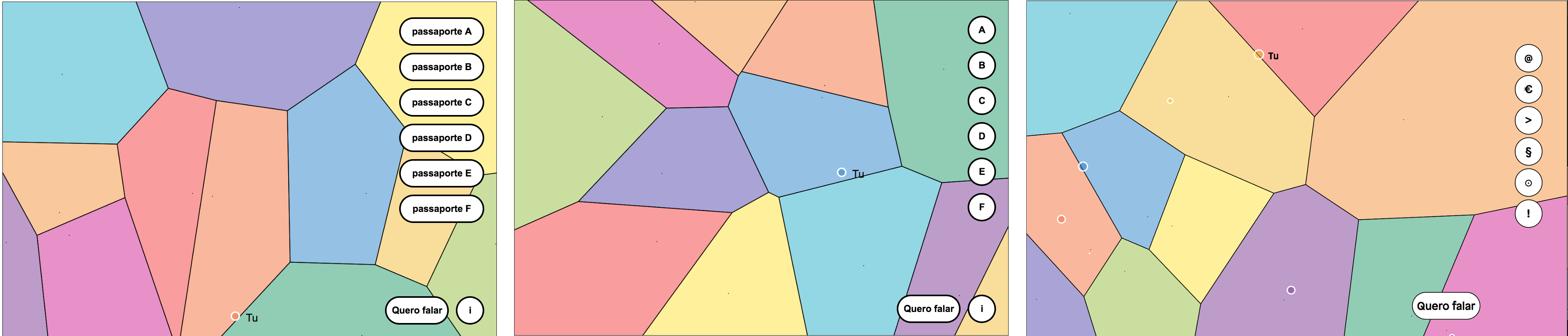

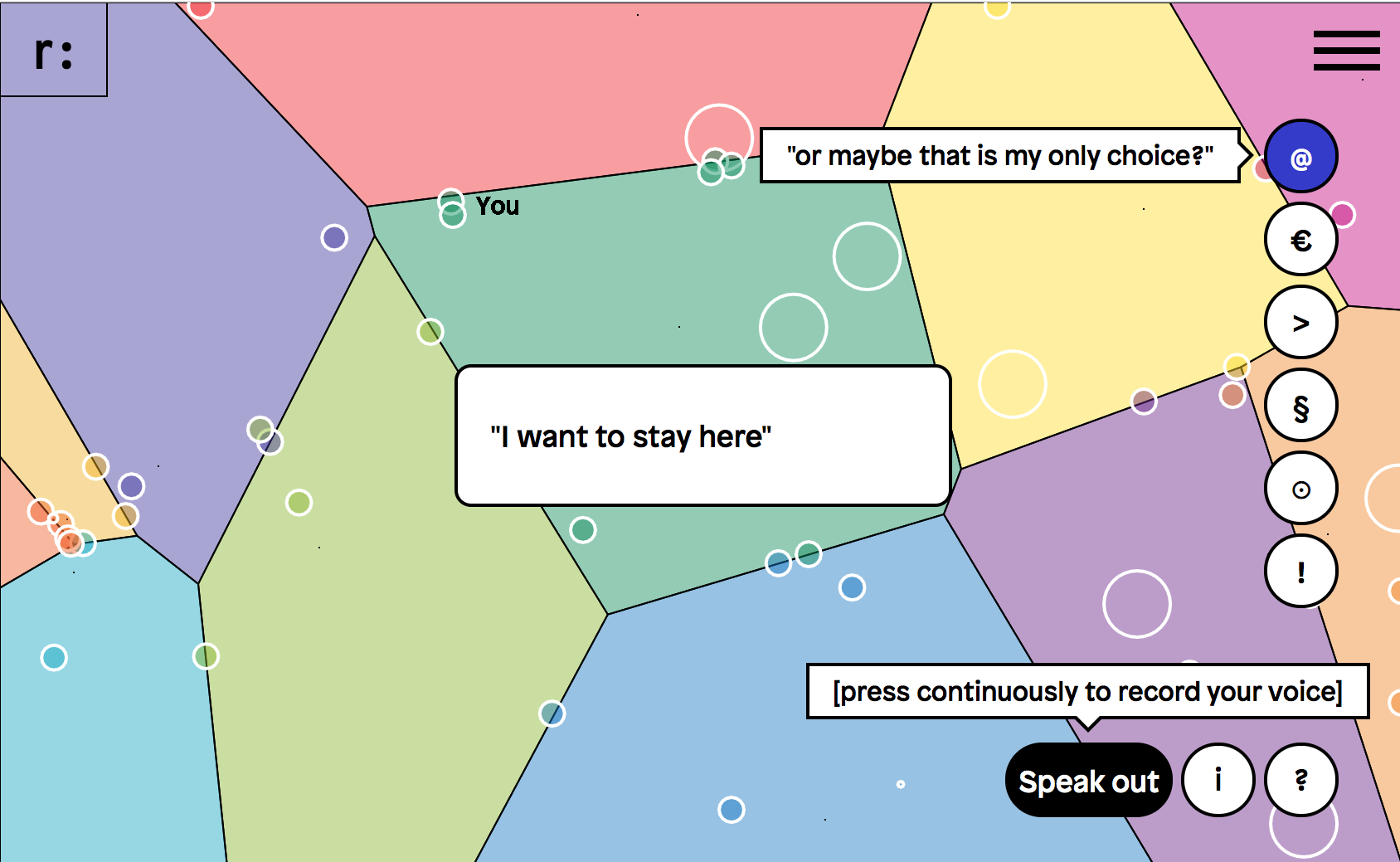

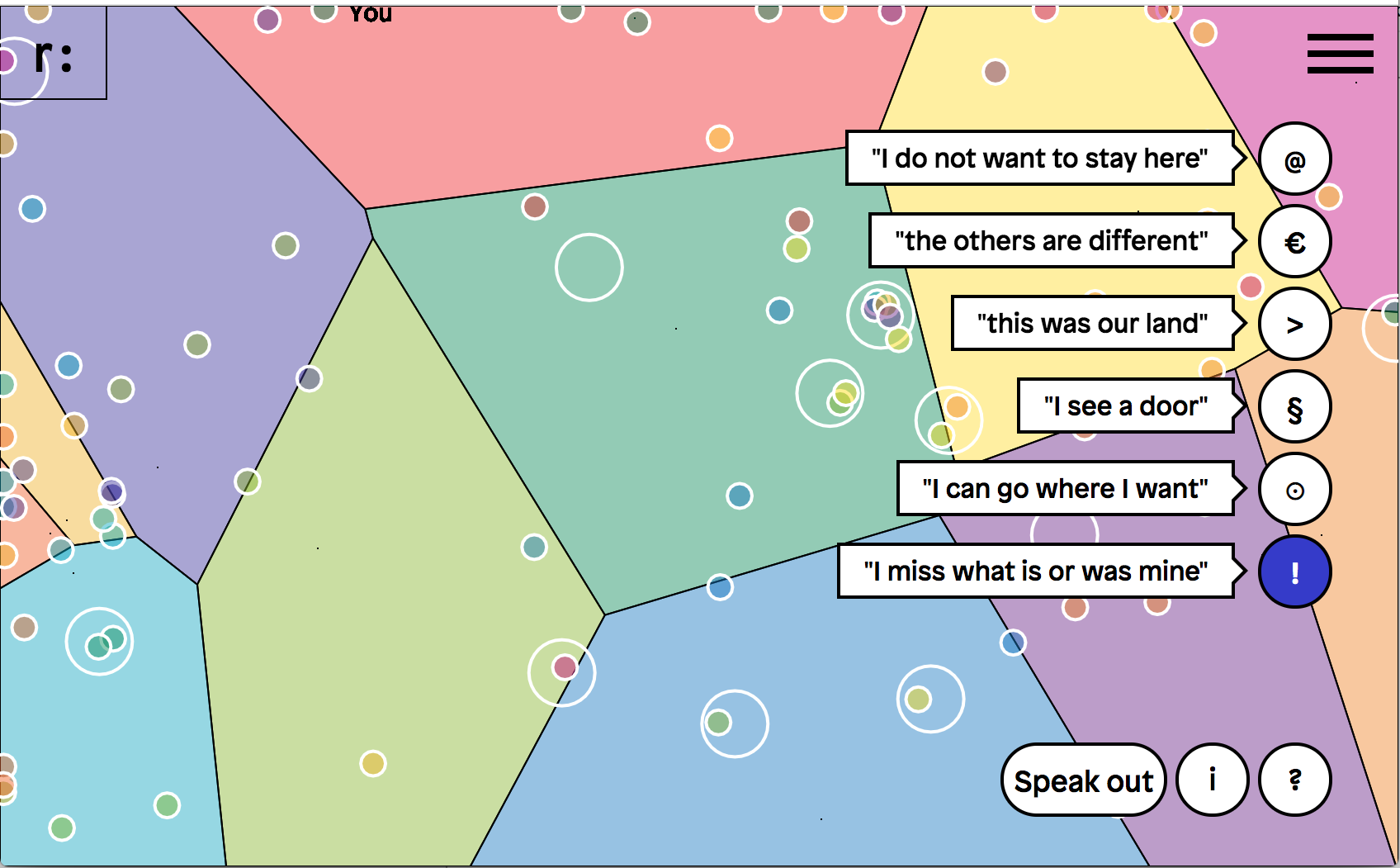

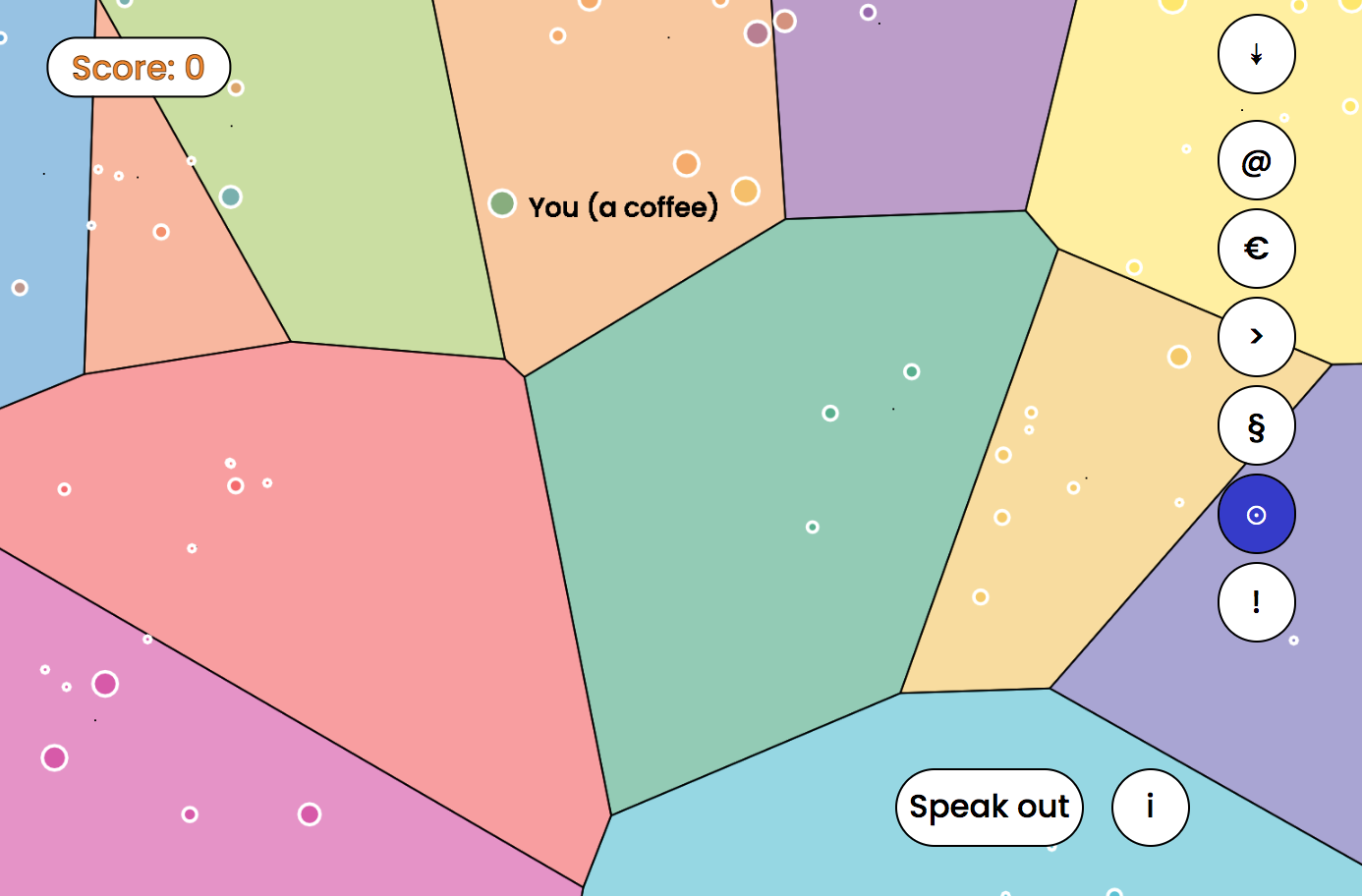

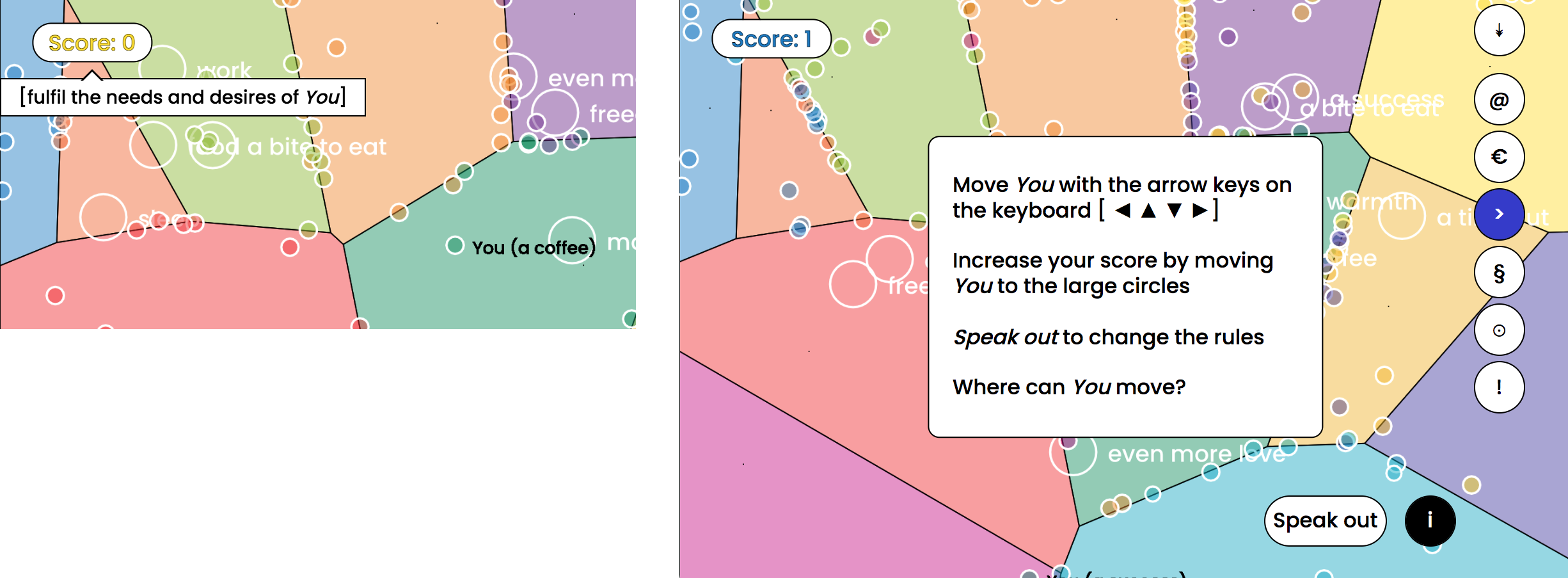

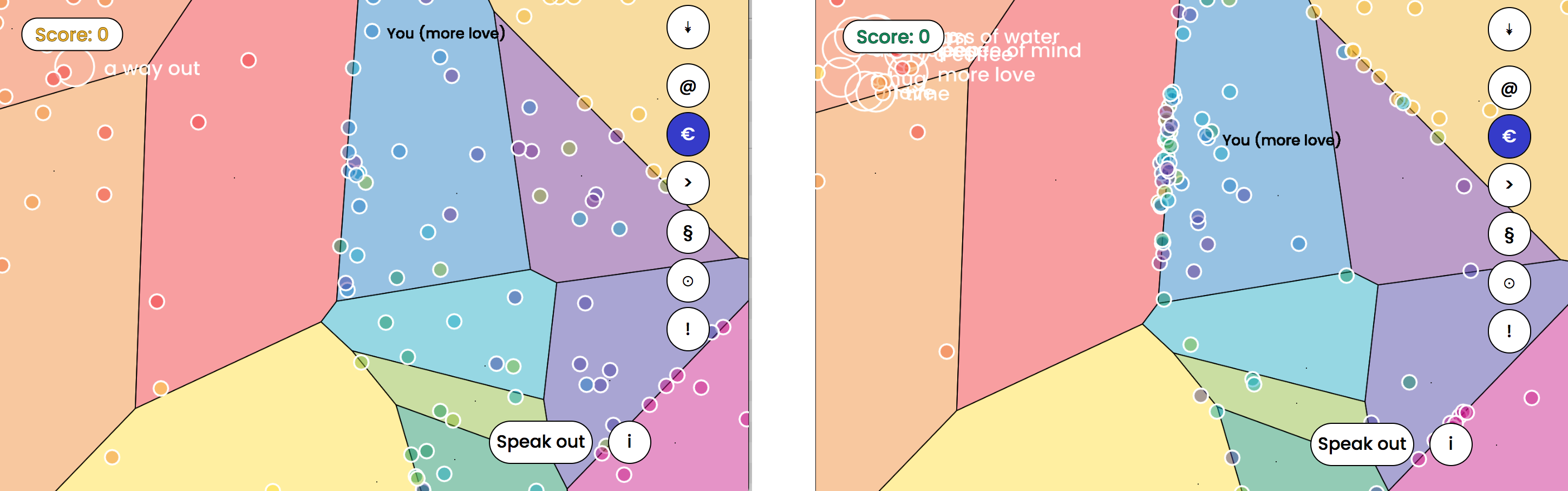

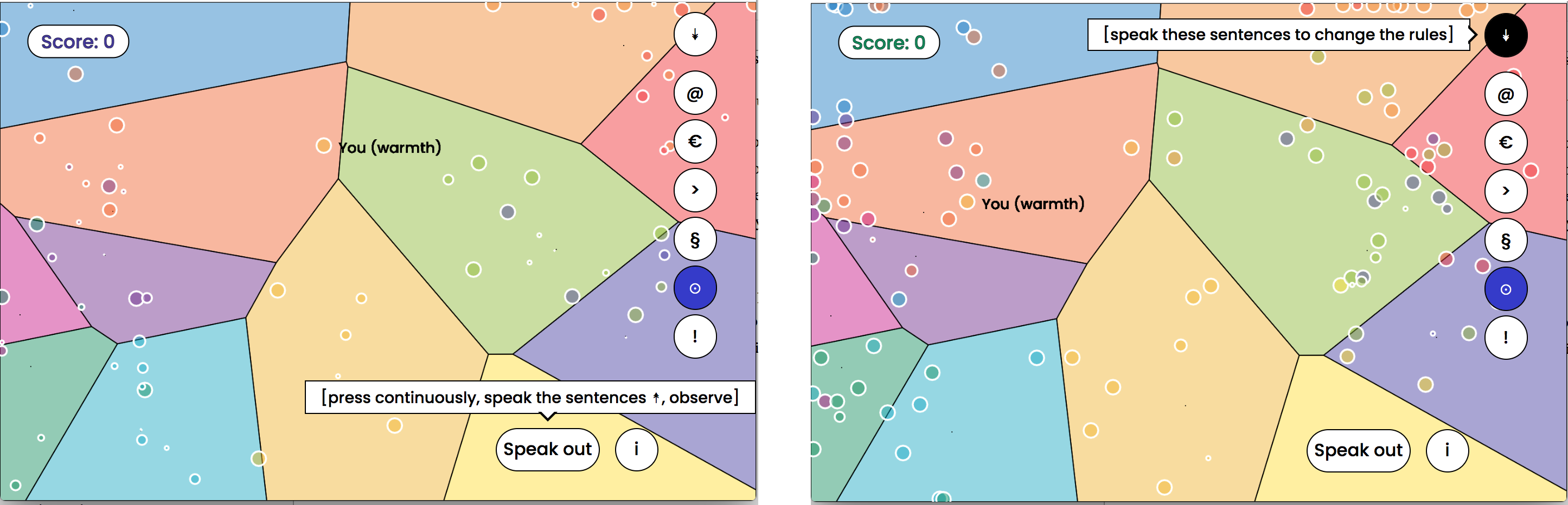

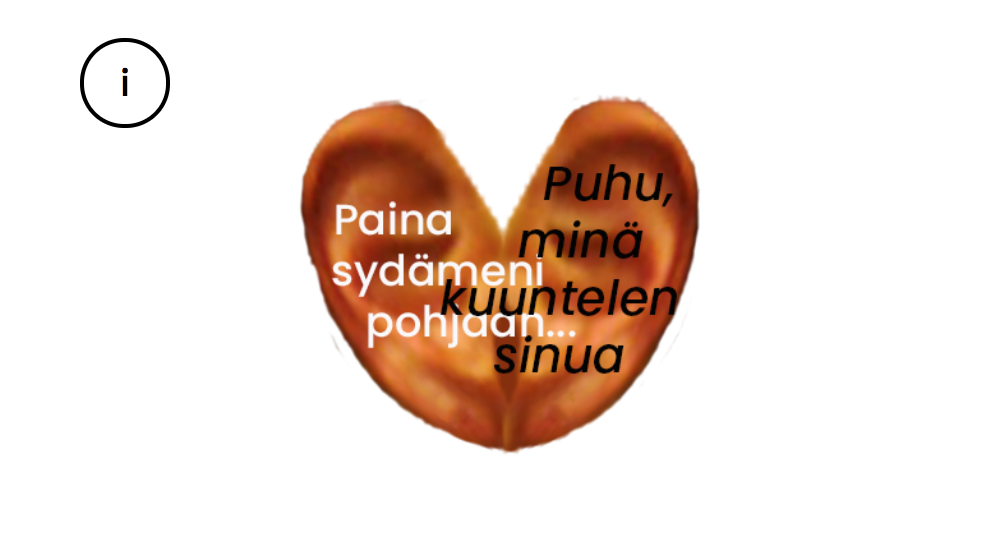

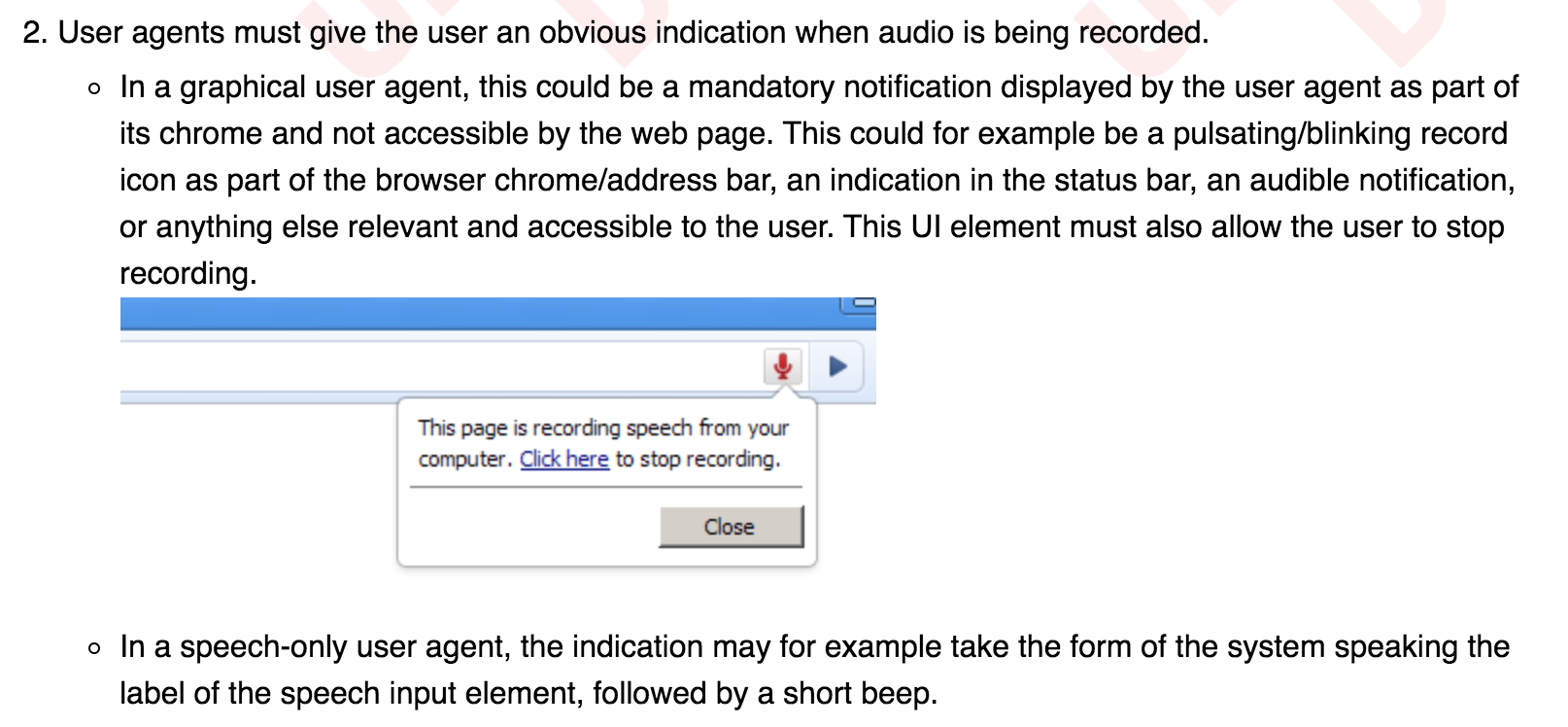

The themes encompassed extend from exploring perspectives on language, where movement results in linguistic accent which provokes a notion of the Other through external difference (in We cannot take them all), or exploring the movement induced by the tension between our body and our personal needs and desires, but that is governed by (shifting) borders (in Speak out) and finally, at exploring migratory movement through the ambivalent relationship between the here and the there, the simultaneous processes of (re-)rooting and of living with homesickenss (in Transplanted).

While this research may not depart from clear research questions, it nevertheless arrives at observations about the artistic strategies that emerge when migration is explored through notions of voice/interaction. The works themselves open up a space of contemplation about the respective themes, inviting participation through voice.

Keywords: migration, voice interaction, electronic literature, digital art, artistic research

☉

Resumo

Neste processo de investigação artística, parto da idea de uma obra de arte digital como ferramenta para imaginar e brincar com realidades (ainda) impossíveis, para formular questões e para retratar aspetos da vida de forma a serem exploradas à distância.

Esta dissertação é constituída por três obras interativas desenvolvidas por mim para o navegador web, programadas em HTML, Javascript e CSS. Estas experiências desenrolam-se no ecrã, mas contêm sempre um papel essencial para o utilizador. As obras incorporam, entre outros, a interação por voz através da voz sintética e reconhecimento de fala, o uso dos quais constitui sempre uma estratégia artística fundamental em relação a temática de cada uma das obras. As três obras têm temas diferentes, mas em conjunto, contemplam o significado do movimento causado pela migração, do ponto de vista humano.

Os temas abrangidos derivam da exploração da língua em si, em que o movimento produz um sotaque lingüística que depois provoca a idea do Outro através desta diferença externa (We cannot take them all), ou a exploração do movimento em si, provocada pela tensão entre o nosso corpo e as nossas necessidades e vontades pessoais, mas que é governado pelas regras sobre as fronteiras, que em si estão em fluxo constante (Speak out), ou a exploração do movimento migratório através da relação ambivalente entre o aqui e o alí, os processos simultâneos do enraizamento e o viver com saudades duma terra deixada para trás (Transplanted).

Embora esta investigação exploratória artística não parta propriamente de questões pré-estabelecidas, acaba na mesma por desenterrar algumas observações sobre estratégias artísticas à volta da migração no contexto da interação por voz. As obras em si criam um lugar para a contemplação sobre os respetivos temas, convidando a uma participação através da nossa própria voz.

Palavras chaves: migração, interação por voz, literatura digital, arte digital, investigação artística

☉

Acknowledgements

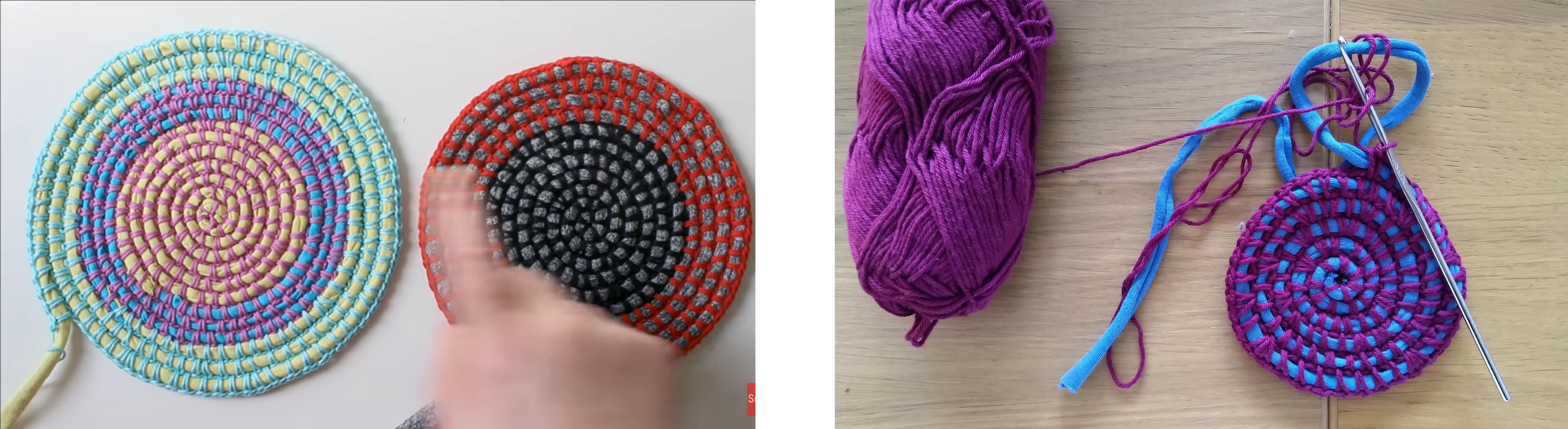

My deepest gratitude goes to my supervisors Professors Patrícia Gouveia and Diamantino Freitas, both essential in their guidance, and for providing me with opportunities to grow from seed to sprout in the profession of an artist-researcher. I am thankful to Professor Mirja Hiltunen from my alma mater for encouraging me to pursue doctoral studies, and to Professor Satu Miettinen for inviting me to join in the group exhibition Growth, Death and Decay that resulted in the creation of Transplanted. To Michelle Kasprzak and Claudia Laranjeira for proofreading pats of this manuscript. A huge thanks to Professor António Coelho who has always made things possible, and to Marisa Silva who solves all problems.

An enormous thank you to João Sousa (v-a studio) who contributed valuable graphic and interface design for Speak out during the raum.pt residency. Diogo Cocharro for support in the sound design of Speak out and for recording engineering for Transplanted. Thank you to Joseph Carens for blessing my transposition of his thinking into We cannot take them all.

When the Electronic Literature Organisation (ELO) hosted a conference in Porto in 2017, I felt I had finally found my artist-researchers spiritual home for the language-based practices that attract me. I am deeply honoured to have my 2016 work Give me a reason included in the upcoming Electronic Literature Collection 4. I thank Rui Torres for reading suggestions at early stages in my research process, Nick Montfort for taking the time to come see my presentation, Annie Abrahams for taking an interest in my work. It means a lot to be seen and heard by those whose work I admire. This community continues to inspire me.

I am forever indebted to my sibling Tero for being my mentor and patron saint

of programming: in the early days, an extension of stack overflow, in the past for refactoring my code and teaching me new coding principles, and for always being ready to help. Tero even promised to do my coding for me if need be. Curiously, that reassurance was enough for me to try my own wings. Furthermore, I still remember the look on the face of various engineering faculty members from the University of Porto when I expressed my doubts about being able to program my own ideas. Their faces always read: what on earth are you talking about?

. This look was accompanied by a comment along the lines of you can do it, it is easy

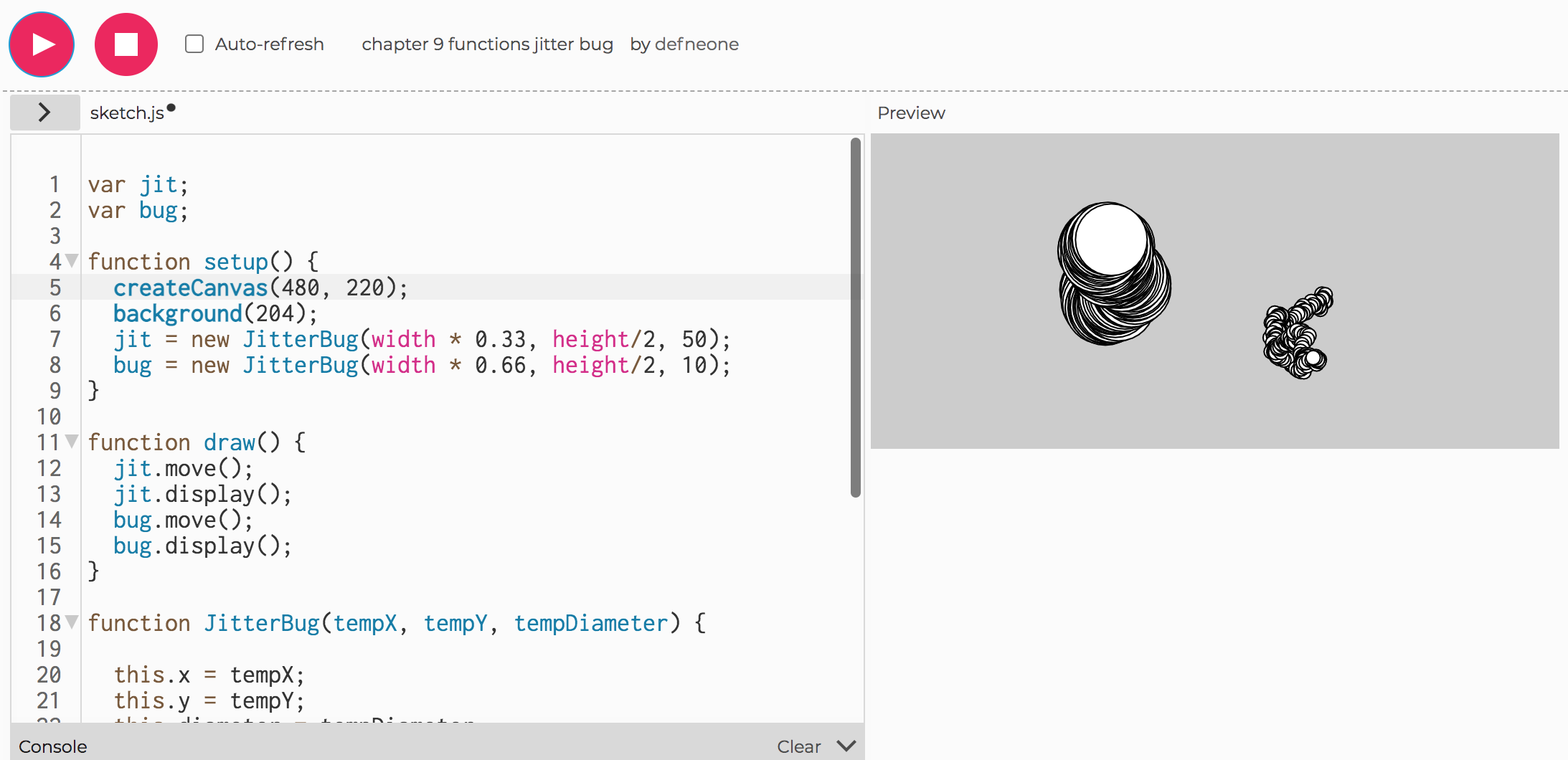

. Having this support and belief from practitioners of programming has been essential for demystifying the practice and for creating a sense of inclusion. p5.js itself (created by Lauren McCarthy), as well as the community around it and especially Daniel Shiffman’s The Coding Train videos were essential for allowing me to translate my visual idea about migration as movement into code. I laud the inclusive approach of the processing and p5.js community, and acknowledge its enormous impact on my practice.

Much thanks to my doctoral cohort in digital media 2016. To the universe and Kika for the chain of random events that brought me to Porto. Michela Magas and Andrew Dubber for organising the Music Tech Fest, since attendance at the hackathon in Ljubljana in 2015 solidified my resolve to pursue my dream of learning to program. Ana and Sandra, who cushioned my landing in Porto. Renu, for friendship and for collegial support. Kati for constant support and presence and Mirjam, the Girls Dinner group, have all made life more fun. Carla, Mafalda and Heldér. Johanna, since 1992. Tero (<3^2). My parents for the innumerable ways they have supported me along this way and all the way leading up to it. Diogo and Lili, whose importance I cannot even begin to put into words.

I acknowledge and am thankful for the financial support by Operation NORTE-08-5369-FSE-000049 co funded by the European Social Fund (FSE) through NORTE 2020 - Programa Operacional Regional do NORTE, as well as the in kind support of the raum.pt platform as well as the ITI/LARSyS research center.

Fonts used are Lora by Olga Karpushina (OFL-1.1. License, Lora-Cyrillic) and Montserrat by Julieta Ulanovsky (OFL-1.1. License, Montserrat).

This dissertation is published as an audiobook and a webpage (with documentation of the artworks as well as the works themselves) at terhimarttila.com/migration-as-movement. ☉

Introduction

When 2015 onwards various European countries saw an increase in the number of asylum requests, public discourse around migration boiled over. These discourses were in response to a tangible change in migration patterns which was felt, heard and seen especially in Germany

, the physical perimeter of ground on planet earth [ or: the place

] in which the currents of life had moved my body to [ or: the place or country I was living in at the time

]. The discourse touched deep into my personal experiences, instantiating an ongoing process of artistic research around the ancient phenomenon of the migratory movement of the human species.

A serial migrant myself, I have experienced both the ease of existence when our surroundings assume us to belong, as well as the friction, in at least some of its milder forms, of being where [ in a place

] one does not, so to speak, belong. Even the fact of having traversed a subset of this artistic research path, namely this dissertation, in Porto, is a further contribution to my personal and lived experience of being that foreigner. After five years here, I cringe when I hear myself speak [ == communicate

] in Portuguese.

I write from a position of privilege, a white woman pursuing a doctorate who has lived in several countries and whose migrations have always been easy: my parents were highly skilled, wanted migrants, the right kind of migrants. My personal migrations have been either inside the European Union where borders (for all practical purposes) do not exist, or as a university student under bilateral agreements. In a 2017 doctoral symposium presentation, my presentation title read: Migration is my right, borders an unnecessary obstacle

.

It is from this privileged position that I have come to live a life (like many other privileged white European persons) defined by a kind of effortless migratory movement where it feels as though we are free to move wherever we want. This is a wonderful way to experience life on planet earth, as a human being.

I wrote a poem about a moment which made an impression on me when I was volunteering with the refugees in Germany:

We sat on a park bench,

talking about his future,

his options,

his meagre options,

after an interview I had organised.

Me and him,

suddenly jolted out of structures,

out of the tent and the camp,

out of our roles,

the refugee and the volunteer.

A young woman, and a young man,

sitting on a park bench,

talking about his future,

and I thinking about mine.

His options, my options,

his meagre options, my ample options,

after an interview I had organised.

Me and him,

why and how,

are we so different?

A young woman and a young man,

on a park bench

talking about the future.

10.11.2016

It is this enormous discrepancy between my privilege and the reality of the human beings that I encountered during my volunteer work that brought a kind of fury to the front, asking, how is my migration any different from his migration? How is it possible for another human body to be sharing that park bench with me, yet at the same time there exist some invisible expulsive force exerting such great pressure on that other body, and on that other body only and not on my body, that their presence in this part of the world might after some time become impossible?

☉

The research that unfolds over the following pages is about deconstructing notions of countries, of belonging, of rooting, of homesickness, of borders, migration, language, some of the things that come to accrue a significance and come to define a human being when that human being, in some way or another, propagates from point A to point B. My research approach is artistic research, and I experiment with ways of using the voice/interface (that is: the voice, the interface and the voice interface) to approach my thematic concerns. I am not sure whether this research ever included research questions, or problems, but I believe I have arrived at some insights nevertheless about artistic strategies for exploring migration through repurposing voice/interaction.

☉

Motivation

In my previous artistic research project (MA dissertation) titled Give Me a Reason, completed in 2016, I found myself recording speech and then splicing sentences up to replay single words to create new meanings. Although Give Me a Reason is not part of this dissertation, I will make reference to it at times since some of the themes I touched upon during that process of inquiry continue to echo through this dissertation.

I found the process of creating Give Me a Reason intriguing and wanted to delve deeper into programming, language, audio recordings of speech and the practice of mashing up and recombining language. And what more, some time after completing that project I stumbled upon synthetic voices through google translate. As I played around with the voices, the translations and the texts, I found all kinds of funny uses for the widget which were, importantly, beyond those uses originally intended.

Delineating my PhD thesis proposal, I knew I wanted to continue to explore the theme of human migratory movement through artistic research. I continued to feel attracted to exploring the area of expression that somehow sits within the hazy zone demarcated by speech, texts, language, language processing, interaction and play in digital art.

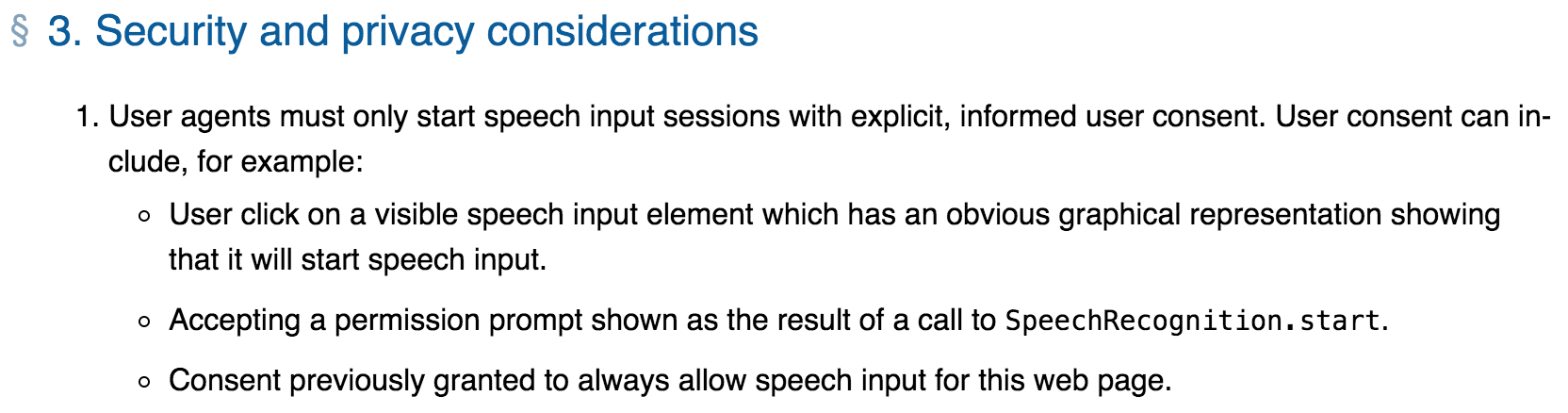

Having worked previously with HTML and Javascript, I soon realised that, although still an experimental technology, the HTML5 Web Speech API would allow me to incorporate the dimension of voice input into my proposed project as well. Thus my inherent fascination with the human voice as material in artistic practice was further expanded as I realised that the modality of speech input was suddenly within my grasp as well. In the final moments of drafting my research proposal, this last artistic constraint made its way into my project proposal: to explore speech input or voice interaction as an artistic strategy.

☉

During my research process, I became curious about how people were experiencing my work, its themes, how they were approaching and experiencing the act of using their voice to interact with the work, and about how they perceived the use of synthetic voice or elements of play in my work. Seeing as the artworks I was creating were interactive, I quite naturally tended towards some degree of informal user research and evaluation in order to make my art work, to make it simple enough such that people could grasp it.

But as the art became usable, I found my conversations with people about my work evolving to addressing how people were making sense of the works themselves, and what types of thoughts or questions the engagement with the works would bring forth, in other words, how the work was being experienced. For this reason, besides the artistic process of iteratively creating the works, I also did an experimental and very small set of observations and interviews that resulted in a small corpus of data about the detailed experiences of some people that engaged with the work.

While this process of studying peoples experience with the works is an important component of this thesis, I still defend that the actual artistic process, and especially the iterative act of writing/composing and rewriting/recomposing code itself as a form of artistic practice and inquiry into human (migratory) movement, have been the most important outcomes of this dissertation. This inquiry through art practice is what guided and structured my entire research process. The practice itself has thus been my method, if we conceive of methods as "tools, tools for thinking with and tools for structuring that act of thinking with (Hannula, Suoranta & Vadén 2014, 37). The hands-on practice and craft of making the work is what led me to uncover important themes related to my chosen artistic approach. I will argue these methodological choices in more detail in the next chapter.

☉

Relevance and context

The title of this thesis suggests at two distinct areas of research: voice / interface and migration. In this section, I will argue that while my practice touches upon both the voice / interface and migration, my research has to necessarily be positioned in a third category entirely. My work is first and foremost about experimenting artistically at the crossroads of these two domains of knowledge. In other words, what types of critical angles can I, as a practitioner, unearth and explore with regards to the complex phenomenon of human migratory movement when I employ the voice / interface in my artistic practice?

Context: migration

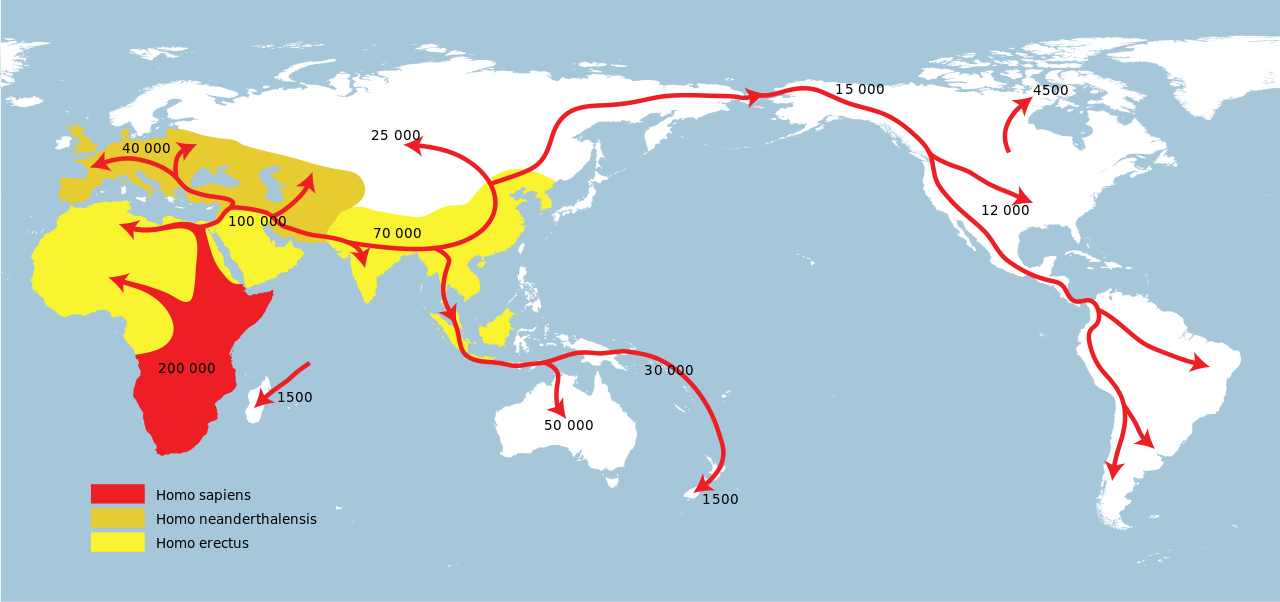

Global migration and the tendency of us humans to move across physical space in pursuit of our life objectives will always be a topic worthy of study whether through our art practice, through artistic research more specifically or through any other research approach. To migrate, to move ones life (semi)permanently across physical space to a distinctly other area of our planet, is a central human tendency which will likely continue to exist. There are ample case examples of these migratory patterns of our species throughout history. To study, through artistic research, the ways in which the migration phenomenon can be conceptualised, or to address through art complex notions like xenophobia, is to further our understanding, in a more open manner characteristic to art, of this very human phenomenon.

Therefore, while my practice revolves around various aspects related to human migration, I can in no way claim that my (artistic) research will contribute towards any new understandings about migration in the sense of academic knowledge creation. Although I have immersed myself in books, journal articles and other academic texts published in various disciplines outside of the digital arts, areas like sociology, politics, philosophy and history, I acknowledge that my work will not contribute directly to the academic discourses in these areas.

However, I am highly indebted to these research areas insofar as they have informed my personal practitioner research, which Candy and Edmonds define as the type of research which practitioners engage in which is not shared with the wider community but serves to further the artists’ personal practice (Candy & Edmonds 2018, 66). These readings have challenged my own perception of migration as a complex phenomenon. Some of these insights are to be found in some form in my work, although the purpose of my work is not necessarily to convey any of these ideas.

Moreover, this process of questioning and making sense of the phenomenon of migration is in no way complete, as I continue to stumble upon novel perspectives in my readings. Studying the work of scholars in fields other than mine have definitely broadened my perspectives on human migratory movement. I also follow discussions in the comments section of news items related to migration to probe the types of attitudes and beliefs that circulate or are expressed publicly.

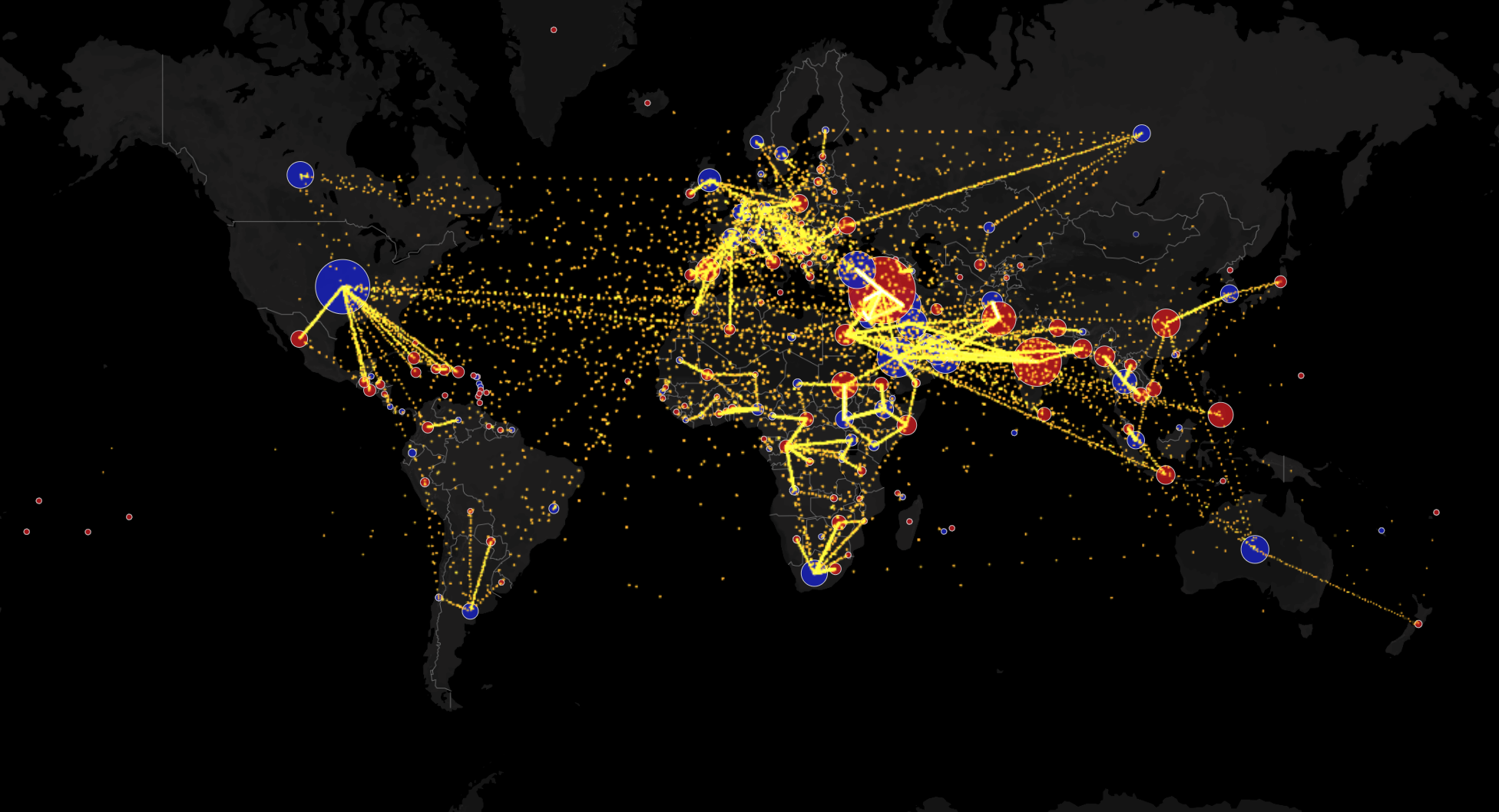

My work is contextualised in a broader realm of art, electronic literature and maybe even games which address a broad range of themes that emerge when we look into the phenomenon of human migration: refugees, language, xenophobia, belonging, adaptation, integration, homesickness, etc. I've found inspiration from a broad spectrum of areas, from data visualisations to sound art, and web-based generative and interactive literature. For the topic of migration, I’ve been more inspired by my readings into political science, sociology and political philosophy than by artworks about migration as such.

Nevertheless, a notable and recent artistic response, with enormous impact, to the perceptions of migrants in 2010s Europe is Olu Oguibe’s 2017 Monument for Strangers and Refugees for Documenta 14. The Obelisk was erected in a central square in Kassel, at Königsplatz, with inscriptions in the four major languages spoken in the city: German, Turkish, Arabic and English. The Obelisk cites a passage from the Christian Bible, Matthew 25:35 which reads "I was a stranger and you took me in. The monument was quietly taken down in 2018, due to political opposition especially by the newly arisen german right wing party AfD, but later, in 2019, re-erected in a nearby square. Bonaventure Ndikung, the curator who invited Olu Oguibe to Kassel, recently reflected on the significance of Oguibes work like this:

What provoked so much tension, so many emotions – varying from excitement to rage – around Oguibe’s monument, besides its conceptual and aesthetic brilliance, was the fact that it was audacious. The obelisk had the audacity to stand on the city’s 18th-century Königsplatz, which was named after Friedrich I, King of Sweden and Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel. The obelisk had the audacity to point at Germany’s Achilles heel: the question of migration. The obelisk had the audacity to reveal the bigotry hidden behind religious claims and democratic flags. The obelisk had the audacity to betray an essential and fundamental unspoken truth in this construct called Germany: that it is a conglomerate of tribes and peoples who fought against each other for hundreds of years. United to combat the Romans in the Teutoburg Forest in 9CE, to form the German Empire in 1871, to repair the devastation of World War II in 1945, and to reunify East and West Germany in 1990, the country’s common denominator – its underlying truth, too often denied – is its strangeness and pluriversality.(Ndikung 2021)

Another intriguing work is Say Parsley (2001 - 2010) by Caroline Bergvall which explores the idea that how you speak will be used against you

(this is the subtitle of Bergvalls work on her website). Bergvall’s work references the Haiti Parsley massacre, in which differences in the pronunciation of the word parsley" were used to distinguish between Haitians and Dominicans in order to send Haitians to their death. This practice in turn echoes the Sibboleth, a biblical tale of how the pronunciation of the word "sibboleth" was used to massacre one tribe. Bergalls work is about how language reveals our origins and also our own prejudices.

Another work which I have found meaningful is Bury Me, My Love (2017), a digital game by The Pixel Hunt. Bury Me, My Love follows the main character Nour on her perilous journey from Syria towards safety in a compelling instant messaging application style format, where we play Nour's partner, who stays behind in Syria and accompanies Nours journey over on his device. The game includes the option of playing in pseudo-real time, which means that sometimes we might not hear back from Nour for a day or two. The game is based on the experiences of Dana, a Syrian refugee, and an innovative concept developed by journalist Lucie Soullier, who published Danas journey from Syria to Germany as a whatspp conversation. Bury Me, My Love is primarily a branching narrative or interactive story, although player choices about how to converse with Nour influence factors like hope, inventory, mood etc., which in turn also affect how Nours journey progresses.

Context: voice / interface

Another important influence and context for my work is the creative use of the voice and voice interaction. I have familiarised myself with the technological development of the voice / interface, immersed in some of the academic debates around voice interaction in the areas of engineering, sociology, human computer interaction and so forth, yet, I am conscious that my work will not contribute directly to these debates either. I have not solved any major engineering problems, nor have I provided solutions for the ethical issues around voice technology. Nor does my work provide a critical angle on technology and voice interaction. Outside of the context of the creative repurposing of the voice/interface, my work may at most be able to contribute new ideas and knowledge in the context of human computer interaction.

Finally, the context and relevance of my work is to explore some unexplored avenues in the creative use of voice, of language and of voice interaction to talk about migration. I do so by employing notions of procedural rhetoric (Bogost 2007) and play (Sicart 2014) as a way to understand in part the role of speaking in the context of my work. I also discuss my own code through the lens of critical code studies (Marino 2020), showing how the rhetorics of my work also exist beyond the surface and on the level of code, in variable and function names and in my decisions of how to program the relationships within my systems.

My work is situated within the area of electronic literature, where creative practitioners working in the digital language arts have already explored the use of voice and voice interaction in various kinds of contexts throughout the last two decades. The relevance of my work is likely to be greatest in this area of research.

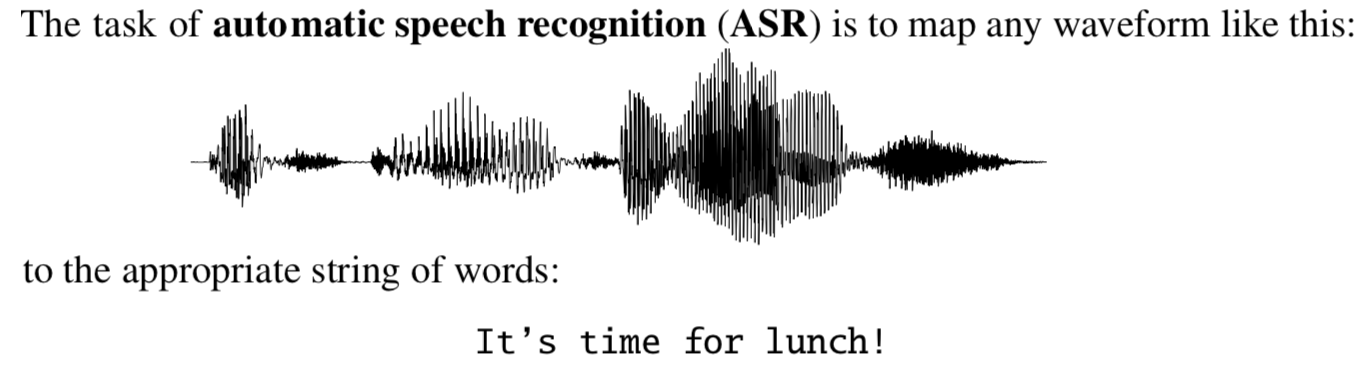

Voice user interfaces have been a subject of study for engineers and computer scientists for decades, as they have tried to figure out how to interface with computers through speech and natural language. With voice user interfaces becoming more prevalent in recent years, user interface designers have also highlighted some of the design considerations for designing voice user interfaces (see Pearl 2017). In the realm of videogames, worthy of mention is Allison’s 2020 PhD thesis titled Voice interaction game design and gameplay, which is concerned with the phenomenon of voice-operated interaction with characters and environments in videogames

(Allison 2020).

A highly effective and appropriate use of synthetic voice is in Kıratlı and Wolfe’s (in collaboration with Bundy) work Cacophonic Choir (2019). The artists collected sexual assault survivor stories from the The When You're Ready Project, a community for survivors of sexual violence to share their stories and have their voices heard, finding strength in one another

(Wolfe, Kıratlı and Bundy 2020) and trained neural networks on these to create new stories based on these. The stories could be listened to by moving close to lighted sculptures, which would then begin to read the texts in a synthetic female voice. In my opinion, the use of the synthetic voice is appropriate because it anonymises the difficult stories about sexual voices, yet at the same time brings some element of the human through the synthetic voice. For me, listening to video documentation of the work online, I cannot help but also think of how the eerie, disturbing and unnatural synthetic voice acts as a reflection of the eerie and disturbing nature of sexual violence.

Early forays into artistic experimentation with voice user interfaces go back to the late 90s and early 2000s in the works of Ken Feingold and Stelarc, among others. I will look here at Feingolds work in particular. Huhtamo writes like this about the work of Feingold:

He uses state-of-the- art technologies not as goals in themselves (as some ‘artist-engineers’ do), but as means of reflecting on their social and psychological meanings – particularly the anomalies and paradoxes that always accompany their implementation, including the question about ‘poorly designed’ or ‘badly working’ technology.

(Huhtamo 2019)

In many ways, Feingolds works are in my opinion some of the most interesting when we consider works that employ voice/interaction in a broad sense exactly for the reason that Huhtamo refers to in the quote above: because the technologies are used as means of reflecting on their social and psychological meanings

(Huhtamo 2019). By my personal experience of wandering around in the art context over the last ten years or so, I note that the use of synthetic speech is increasing, and that I am also ever more frequently stumbling across artworks, especially online works, that employ speech input in some manner. However, a vast majority of works use speech simply as a means of inputting data or as alternative to pressing a button without dealing deeply with the implications of the act of speaking or the machine/voice itself.

Feingolds series of works dating to the turn of the millennium are especially interesting because of the multiple ways in which they explore human relationships, conversation itself, language and metaphysical questions of existence through the use of sculpted robotic human heads, voice, synthetic voice, voice interaction and speech recognition.

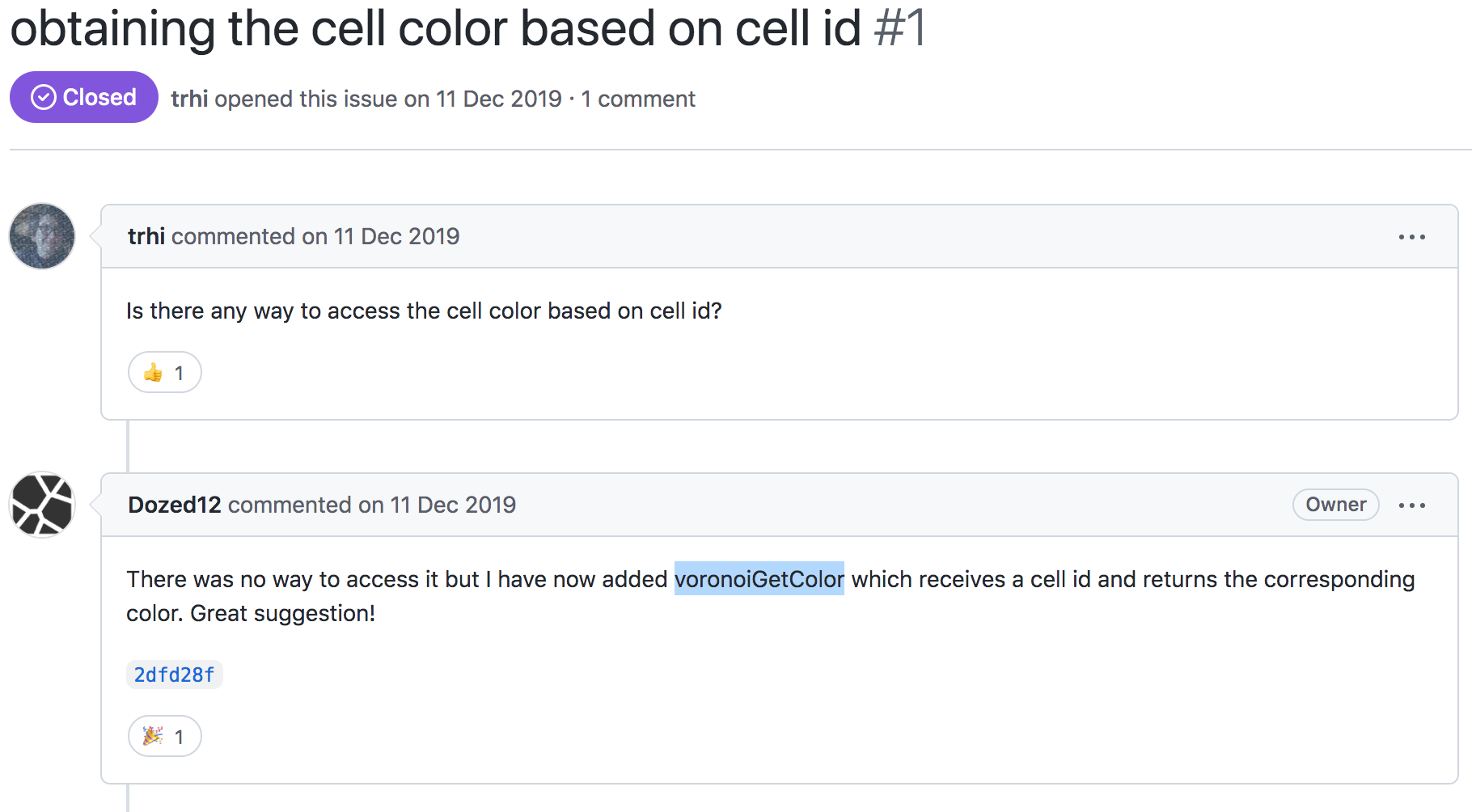

Figure 1: If/Then (2001) by Ken Feingold, screenshot of video documentation (Feingold 2011a)

Feingold describes the work If/Then (see figure 1 above, previous page) in the description section of the video documentation of the work on his YouTube channel as follows:

Two identical heads, sculpted in the likeness of an imaginary androgynous figure, speak to each other, doubting the reality of their own existence. These two, in ever-changing and outrageous conversations with each other struggle to determine if they really exist or not, if they are the same person or not, and if they will ever know. I wanted them to look like replacement parts being shipped from the factory that had suddenly gotten up and begun a kind of existential dialogue right there on the assembly line. Their conversations are generated in real time, utilizing speech recognition, natural language processing, conversation/personality algorithms, and text-to-speech software. They draw visitors into their endless, twisting debate over whether this self-awareness and the seemingly illusory nature of their own existence can ever be really understood.

(Feingold 2011a)

Feingold alludes to the human through the sculpted head of course, but perhaps more importantly, through the use of speech and the voice. What I think is interesting about If/Then is Feingold’s artistic take on the discrepancy between our perception of the synthetic voice as somewhat human, especially when it engages in a conversation, and the impossibility of a machine ever being a human. Moreover, albeit the voices sound female, the heads themselves are sculpted purposely as androgynous, which in my perception critiques in an elegant manner our propensity to attribute humanised computer characters with gender.

Figure 2: The Animal, Vegetable, Mineralness of Everything (2004), screenshot of video documentation (Feingold 2011c)

In other works, such as Sinking Feeling (2001) and The Animal, Vegetable, Mineralness of Everything (2004) Feingold appears to have sculpted the heads to resemble his own (see figure 2 above) which I also find intriguing as it makes visible his authorship of the movements of mind of these humanoids. In these two works, the robots are Feingold, quite literally.

In a work form 2004 titled You (see figure 3 below, next page), two androgynous heads, one with a male voice and the other with a female voice, engage in an ever-ending generative argument about their relationship. As Feingold writes:

We see how oft-repeated phrases can have little real meaning, but a lot of power to do harm. The endlessness of their predicament is literally programmed and self-perpetuating, going nowhere - perhaps a way to think about those who cannot escape from similar cases.

(Feingold 2011b)

I find Feingold's use of procedures in the case of You extremely intriguing as well. In the work You, Feingold uses the perpetual loop in his code as a metaphor of the toxic loops that inflamed relationships lead us into, some of which are very hard, if not impossible, to get out of.

Figure 3: You (2004) by Ken Feingold, screenshot of video documentation (Feingold 2011b)

Another example is the use of natural language processing (and probably the use of keywords picked up by the speech recogniser) in works such as If/Then (2001) and The Animal, Vegetable, Mineralness of Everything (2004) to create a kind of perception of logical dialogue and continuity between the turns of speech in the meandering and perpetual conversations that these figures engage in. The thoughts expressed by the characters taking turns are interlinked but at times also disjointed, which is a reflection of the complexity and perhaps even the ambivalence of any existential debate. The limited scope of what the characters are speaking about also makes the randomly generated exchanges appear to follow a logical flow.

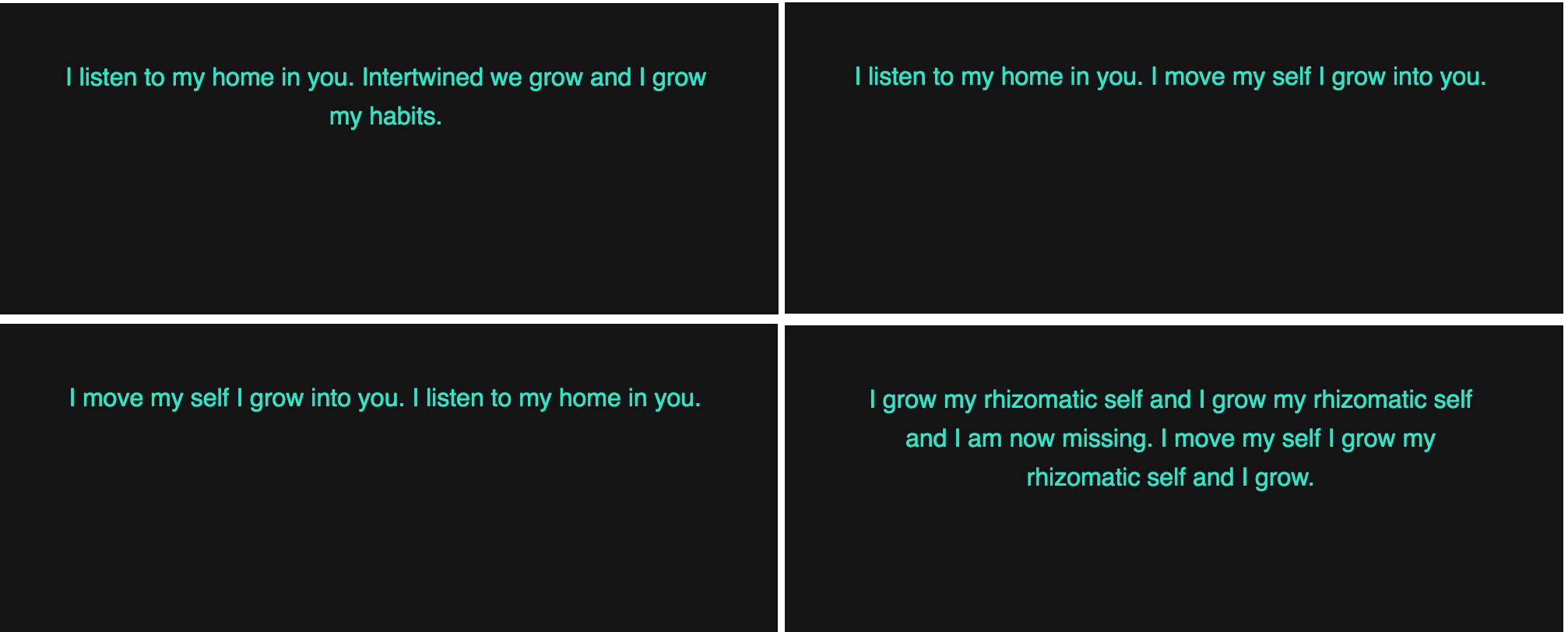

This is a classic approach in the design of any conversational agent, the earliest example of which is the psychotherapy bot ELIZA (Weizenbaum 1966), possibly the first chatbot or conversational agent created. ELIZA mimics the approach of a Rogerian psychotherapist, retorting to any user input with a question that references keywords that the user mentions, or by asking more questions or by saying I understand

. Due to the restricted context and the ingenious inner logics of the program, it can, at least momentarily, feel as though ELIZA really understands what is going on in the conversation: ELIZA shows, if nothing else, how easy it is to create and maintain the illusion of understanding

(Weizenbaum 1966, 42). I use a similar device in my work Transplanted, as I loosely link the feedback of the system to keywords that the person speaks, creating an illusion that the system is somehow making sense of what is being said to it.

☉

A recent project by a group of three artistic researchers (and their collaborators) at the University of Washington took a multidisciplinary approach to exploring voice interfaces in their project Voices and voids (Desjardins, Psarra & Whiting 2021). The researchers looked, through their practice, specifically into ethical concerns related to voice assistants. An ongoing five year research project in the humanities titled Talking Machines (2018 - 2023) by a multidisciplinary group of researchers from the University of Turku is looking at electronic voice and the interpretation of emotions and self-understanding in human-machine communication in 1960 - 2020

(see the Talking Machines project website), indicating that there is growing interest in understanding the place of voice interaction in our society.

Another indicator that the creative use of voice interaction is being explored is creative technologist Nicole He’s course in 2018, 2020 and 2021 at the ITP masters program at New York University called Hello Computer: unconventional uses of voice technology

. He challenges students to come up with creative uses and use cases for voice technology. Student projects include, for example, a beatbox-interface, where the person can drag and drop the words boots

, and

, cats

around to then have the voice synthesiser read these out loud.

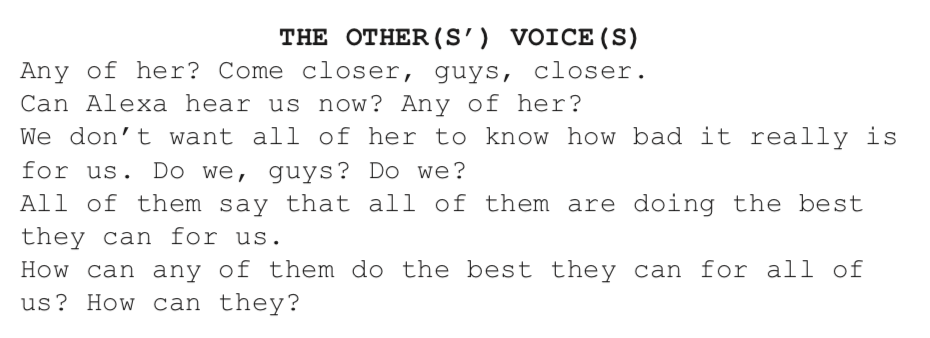

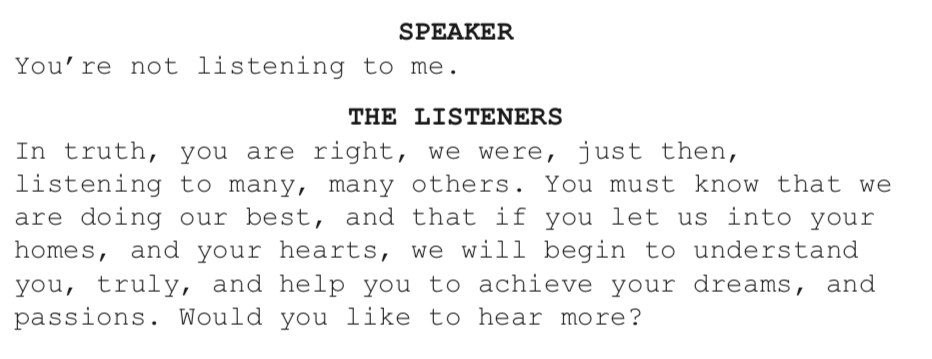

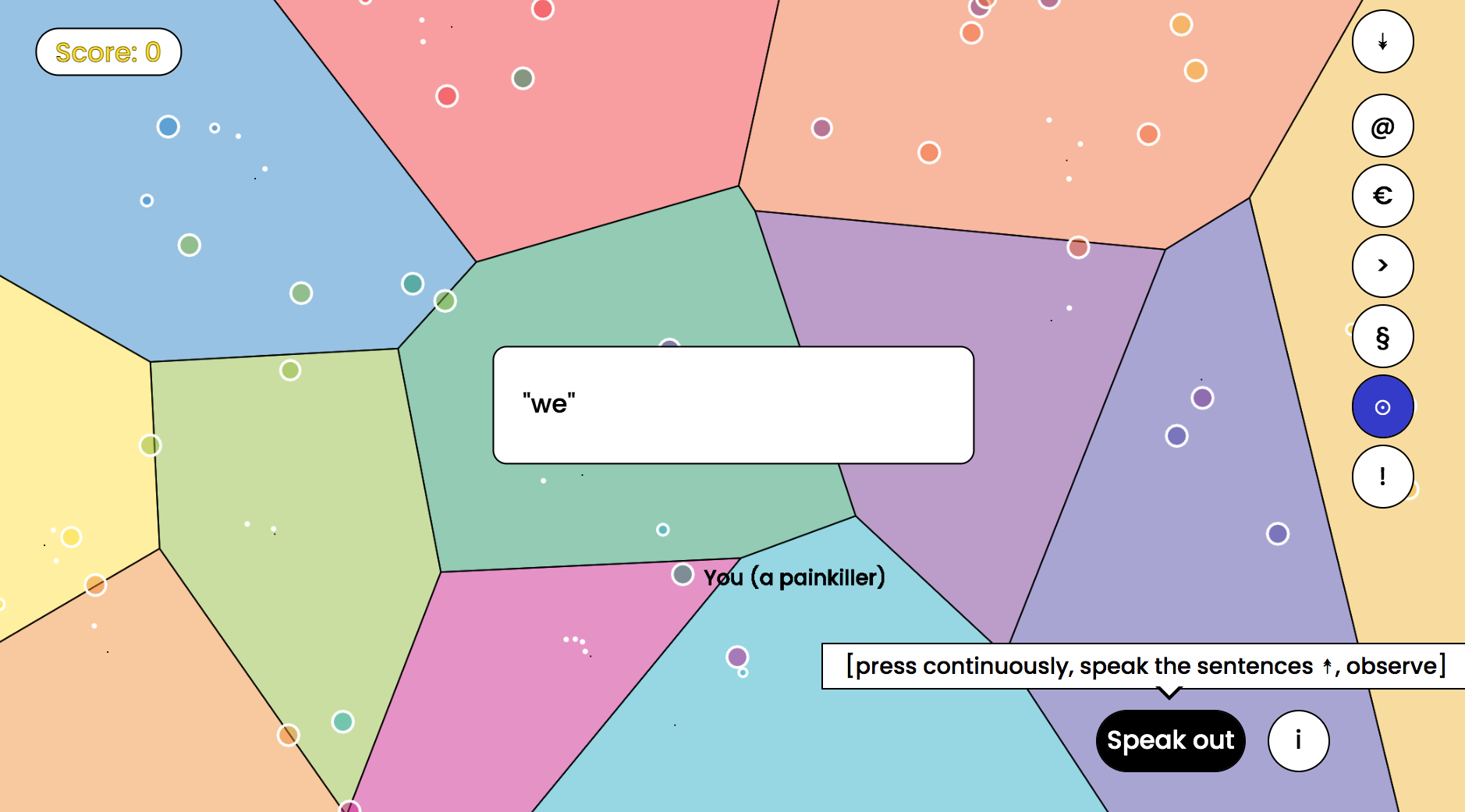

Even Amazons Echo has been appropriated for artistic purposes, in John Cayley’s The Listeners (2015). The Listeners is a somewhat eerie interactive work (something between a conversational agent and branching narrative) for the Echo that, in a subtle manner, sketches the idea of the smart home speaker as a networked device that actually listens to its users in a manifold sense: if you let us into your homes, and into your hearts, we will, in time, understand you truly, and help you to achieve your dreams, and passions

(excerpt from Alexa speaking in The Listeners). Besides an experimental artwork, Cayley’s The Listeners is a product of Cayley’s theoretical-practical inquiry into the future of electronic literature. Cayley suggests that we may be entering an era of aurature:

Aurature. Linguistic work valued for lasting artistic merit that has been expressed in the support media of aurality.

—Based on the OED definition of literatureAurality may be understood either as the entirety of distinguishable, culturally implicated sonic phenomena or, more narrowly and with specific regard to aurature, as the entirety of linguistically implicated sonic phenomena.

Aurature must be distinguished from oral literature (in orality or oral culture), for at least two reasons. In the first place, to emphasize that aurature comes to exist more on the basis of its being heard and interpreted rather than on the circumstances of its production (by a mouth or speaking instrument) and secondly, for historical reasons, because contemporary digital audio recording, automatic speech recognition and automatic speech synthesis technologies fundamentally reconfigure—in their cumulative amalgamation—the relationship between linguistic objects in aurality and the archive of cultural practice. Whereas, during the literally pre-historic period before writing (before there were linguistic objects as persistent visual traces), essential affordances of the archive were denied to oral culture, in principle, the digitalization of the archive allows aurature to be both created and appreciated with all the historical affordances and the cultural potentialities of literature.

(Cayley 2017)

Were Cayleys projections about a new era of linguistic culture in aurality to come true, it would suggest that the materiality of speech and voice interaction merits the scrutiny of researchers and practitioners in the creative arts, whether coming from the angle of literature or digital arts or something other entirely.

Aims and objectives

The initial driving force in this artistic research process was the desire to critically address the topic of migration through digital, interactive art. Besides this general mission, and as is characteristic to artistic practice, the initial aims and objectives of this practice-based research process were vague. I felt attracted to exploring the use of voice because of my past work, and saw my research interest growing into exploring synthetic voice and voice input as one of the means of addressing the topic of migration. The central aim of this thesis came to be to explore aspects of migration through artistic research and (as a by product) to build, through this practice, a richer understanding of the medium of the voice / interface from the perspective of a creative practitioner and in my particular thematic context of migration.

Over the course of my artistic research, and as I put together three distinct projects about migration where the voice / interface played an important part, I felt myself ever more drawn to the voice interface as a medium. I became fascinated by the many ethical issues related to this technology that is slowly finding a place in our everyday lives. So as I conclude this research process and write up this dissertation, I realise that, as is true to any research process, mine has led me to a redefinition of my initial research aims, objectives and even questions.

Research Questions

To my utter surprise, what this artistic research process has led me to are research questions that will be worth asking about the ways in which we contextualise human migratory movement and about the creative use of the voice / interface in the context of migration, rather than conclusive answers to any initial research questions. By keeping my senses open to what my theoretical readings, my practical work and my engagement with persons who interact with my works has revealed, I find that my initial questions were uninformed. The main research question which put my research process in motion was:

In primarily voice-based digital art, what are the main design considerations that lead to a playful and engaging experience which simultaneously raises awareness about the issues inherent in the work?

In the course of my research process, this initial question has eroded because it does not tackle the most interesting issues at stake. Rather, my process has caused new research questions to emerge. The reader may not find concrete answers to these questions in this dissertation, but rather, will see how the research process has led up to these refined research questions. Nevertheless, some of the questions which guided my practice could be formulated something like this:

As artists, what are the questions that we should be asking about the medium of the voice / interface?

and,

What are some of the worlds of meanings contained within voice, language, and voice interaction with computers that I as an artist can leverage to talk about the topic of migration?

and, most importantly,

What are some of the transdisciplinary perpectives on human migratory movement that could truly enable us as artists and thinkers to depoliticise and to reconceptualise migration as movement?

☉

Dissertation outline

Following this introduction, we would typically encounter a series of chapters delineating the research context (literature review or state of the art), elucidating the prior work in the field, the central challenges, debates and terminology. The purpose of these chapters would be to bring the reader on par with the readings of the author. Having attempted multiple times to write these chapters, I eventually had to give up because of one important reason. Because my methodology is practice-based, my research process has been driven by the artistic practice itself. That is to say that one of my first steps in the research process was to start programming. This I did after being inspired by some readings about the ethics of immigration.

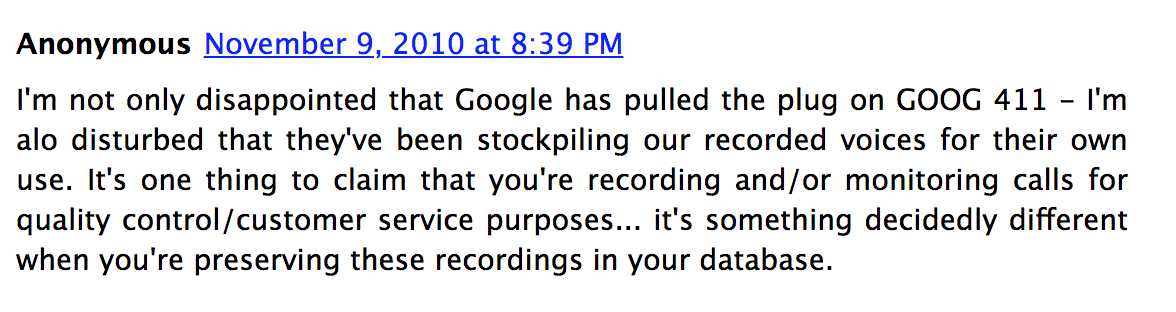

As I worked, themes began to emerge. Before coding a rule into my system, I had to take a step back to think about what kind of a statement I wanted to make about migration. I had to think about why I design my interaction a certain way, what is the meaning embedded in making people engage with the work in a specific way. I stumbled upon privacy issues related to my chosen technologies, and realised that there was already an active ongoing debate about these issues both in technology and in the arts. My understanding of the theoretical and thematic context of my work grew in the process of working. My work does not emerge out of these contexts, rather, the contexts reveal themselves as a result of my practice.

Some of these realisations and trajectories became side paths that are not necessarily evident in the works themselves, yet seem very important from the perspectives of both migration and voice / interaction. For this reason, I have decided to begin this dissertation by discussing my work, so that the reader will understand the work and end by contextualising my work in the discussion, limitations and future work which follows. The discussion is like a collection of essays about various phenomena which my practice revealed. This discussion is extended in the limitations and future work section, where I probe into areas of inquiry which began to seem interesting and relevant during this exploratory research process.

But before addressing the works completed, I will take a moment in the next chapter to argue my methodological approach to this research. I will argue for how my artistic practice, along with this written dissertation, is to be considered research. I will also elucidate what is meant by exploratory programming as a form of artistic practice, and talk about my artistic approach to the voice/interface. I will explain why and how I chose to observe and interview a small sample of people about how they make sense of my work.

After so doing, the practical work will take the lead, each in their own chapters, and discuss their unique context, or the artistic inquiry that led to their becoming. I will then detail the iterative artistic process, highlighting decisions and observations made along the way. After narrating the artistic process and the decisions made along the way, I will reflect critically on the works. After thoroughly presenting my artistic work, I will engage some of the global or overall themes which emerge in the aforementioned essay collection -like Discussion.

Because my research has been exploratory, I have become aware especially towards the end of my process of the many gaps which I could have addressed but did not, each of which is like a black hole, inviting me with force to pursue its concerns in future work. I think that in many ways, these limitations and areas for future work are, alongside the artworks, some of the main outcomes of this research due to my practice-based exploratory approach. For this reason, I have designated a chapter solely for the discussion of these issues.

Following the discussion of imitations and future work, the reader will find me tying off my narrative in the Conclusion. In the appendix, we find a list of dissemination and publications related to this research, the research participation form, notes on where to find the source code of my work, an essay about voice interfaces and some comments on selected portions of my code.

☉

Finally, an important note to the reader, which will be reiterated throughout this thesis. This dissertation is written to accompany three distinct artistic productions, We cannot take them all (2019), Speak Out (2020) and Transplanted (2021). I do my best to describe the works, in chapters two, three and four, but because all works are interactive, they will necessarily need to be experienced in order to be understood. I strongly urge the reader to experience the works at terhimarttila.com/migration-as-movement, terhimarttila.com, github.com/trhi, or github.com/trhi/migration-as-movement and access the works or their video/audio documentation as well as the audiobook of this dissertation.

☉

☉

1 Artistic research through exploratory programming

One might ask, why an entire chapter devoted to the methodology? Isn’t it enough to describe it in a few paragraphs within the introduction?

. Indeed, it may not always be necessary to spend an entire chapter discussing what was done and why. However, I have struggled to clarify for myself, throughout my entire research process, how it is that what I ended up doing can be considered research. This is because artistic research or practice-based research is still not as established a paradigm of knowledge creation in comparison to other more evolved and senior forms of science. This has been an epistemological struggle and surely also a process of maturing towards the identity of an artist-researcher.

For the reader who is perhaps as bewildered as I was about how artistic practice itself can be research, and about how to approach the written dissertation which accompanies the practice, I invite you to follow my argumentation about how my chosen mix of methodologies and approaches is, I believe, valid as knowledge creation. My hope is that by articulating my own choices, others struggling with these issues as they search for their own unique approach may find yet another documented approach to artistic research.

After arguing for artistic research in a more general sense, I will position my work within the realm of procedural systems, language-based works and voice-based works, as well as position my practice in general as exploratory programming. Finally, I will devote some time to the notion of evaluation in the context of practice-based research in interactive arts and what this can mean from the perspective of knowledge creation.

☉

1.1 Notions of artistic research

There is ample literature on the sphere of knowledge creation within the university context which include artistic practice or art practice as one of the components of the research process, or the endeavour in which the artistic and the academic are united

(Borgdorff 2012, 3). This literature will include various terms and concepts which all denote more or less the same thing, albeit with slight variations. Some of the concepts currently in use in the area of fine arts by artist-researchers are:

artistic research (see Borgdorff 2012), practice-based research (see Candy & Edmonds 2018), practice as research (prevalent especially in the performing arts, see Nelson 2013), practice-led research (see Smith & Dean 2009), research creation or recherche-crèation (used in the French speaking realm, see Paquin & Noury 2020).

Practice-based or artistic research is usually said to date historically to the late 1970s or 1980s (Candy, Edmonds & Vear 2022, 74 — 75; Nelson 2013, 11; Arlander 2013). Candy, Edmonds and Vear point out that:

an important influential factor in shaping the way these initiatives take root and grow is a country’s university system and its regulatory standards, which affect the take-up and expansion of such initiatives. Without a suitable regulatory framework, a legitimate role for the designing and making of artefacts leading to post-graduate research awards is hard to justify. Opportunities for including artefacts in formal research remain limited on a world-wide scale.

(Candy, Edmonds & Vear 2022, 76)

For example, the Finnish national university laws position art universities and art faculties as separate entities from science

universities, meaning that art universities initially had more liberty to define how they would award doctorates. In Finland, art universities and faculties have since the 1980s awarded a Doctorate in Arts (DA or Taiteen tohtori

, TaT) instead of a PhD (Rinne 2016, 17 — 19). Any artworks submitted as part of the doctorate are pre examined and considered as official submissions alongside the written dissertation. This type of artistic research doctorates have been implemented around Europe and the rest of the world at varying speeds. According to a position paper on the doctorate in the arts by the European League of Institutes of the Arts, in general it seems that the tendency around the world is to increasingly adopt art-based PhDs (ELIA 2016).

In this dissertation specifically, I discuss three artworks which are integral to my research process, however, they have not been evaluated or pre-examined as an official submission or component of my dissertation submission. Rather, they are considered and examined through their textual representation in this written dissertation towards a doctorate in Philosophy. It is hoped that jury members will familiarise themselves with the works when evaluating the dissertation as a whole, since the works are available on my website. Yet, in theory, this dissertation could be evaluated solely based on this written submission.

The impetus for conceptualising different forms of art practice as research has also emerged through artistic training migrating from vocational training to universities (Borgdorff 2012, 35; Nelson 2013, 3-4 and 14-15), as well as the inflation of the university degree in general, with the PhD displacing the MFA as a terminal degree (Borgdorff 2012, 35; Nelson 2013, 13), leading to the consequent requirement of a PhD degree for teaching positions (Candy 2020, 238). In the European context, this transition towards a PhD in the arts has also been propelled by the Bologna process which sought to unify the European university degree system (Borgdorff 2012, 31; Nelson 2013, 15-16). The question of consolidating artistic practice and traditional notions of academic doctoral study and research has been widely discussed in the last decades in art institutions the world over.

This discussion is still lively, and has its forum in Journals such as the Journal for Artistic Research (JAR), Nordic Journal for Artistic Research (VIS), MaHKUscript. Journal of Fine Art Research, among others. The Society for Artistic Research (SAR) has developed the Research Catalogue, an online platform which provides a format for artist-researchers to present their work online in a format that escapes traditional page- and print-based publishing formats. Various academic conferences also tackle these issues.

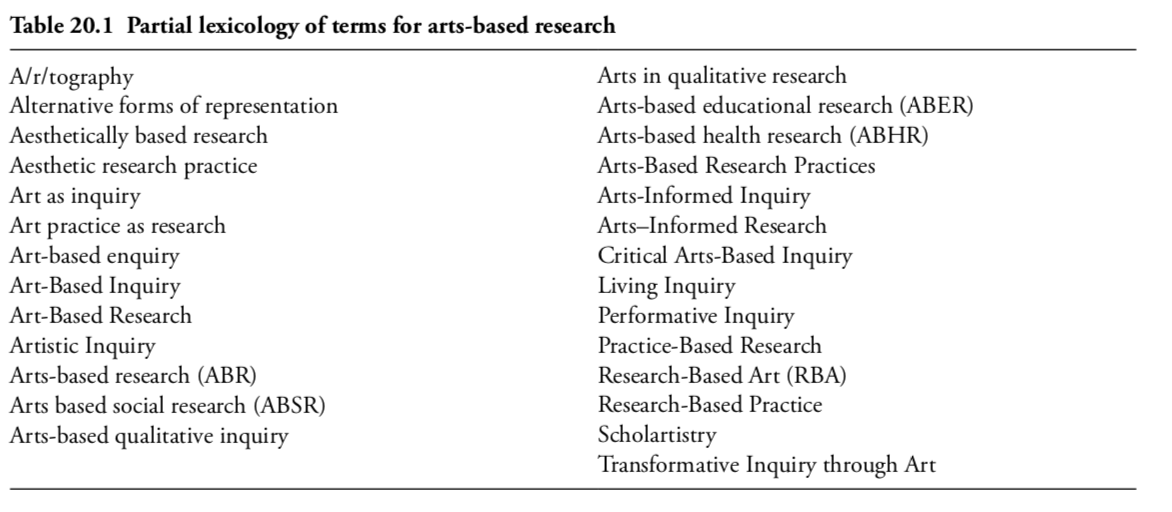

If we expand the discussion of the role of the arts in research into an even broader realm beyond art institutions, then yet more terminology will emerge. Chilton and Leavy collected some of this terminology in 2014:

Figure 4: Table 20.1. Partial lexicology of terms for arts-based research (Chilton and Leavy 2014, 40)

These above concepts and approaches originate from a diverse set of areas of human activity where art, in any one of its many forms, have presence. These terms are thus arising out of areas like music, theatre, dance, literature, poetry, art education, art therapy, education, the social sciences, or the humanities. Behind each concept and within each field there will be differing interpretations and definitions of these terms and about how they contribute to knowledge creation in a research process. Central to these research methodologies as a whole is the notion that either the art artefacts themselves, the artistic process or other art-based practices and approaches can create a unique kind of knowledge which other methodological approaches cannot.

Biggs and Karlsson suggested 10 years ago that artistic research could in fact be a third category beyond either artistic practice or research:

The purpose of training arts researchers should be to prepare them as professionals in arts research. This is not the same as a career in traditional academic research nor is it the same as a career in existing professional arts practice. This is a third professional category that is as yet undefined.

(Biggs and Karlsson 2011b, 423)

Has artistic research become defined over the last ten years? Judging by the breadth of form that the PhD dissertation takes at some art institutions, it seems that arts research has indeed pushed the boundaries of both professional arts practice and academic research.

As an example of a bold approach I cite Otso Huopaniemi's 2018 dissertation titled Algorithmic Adaptations - algoritmiset adaptaatiot (Huopaniemi 2018), which is only published online and not as a pdf. This is because the "written" dissertation contains videos which are quintessencial to understanding Huopaniemis thesis, videos in which google translate and automatic speech recognition is employed as an artistic strategy in writing. The dissertation runs with an english and finnish version side by side on the screen, with the (mis)translation by google translate often available for both texts, again as important evidence of the central arguments of the dissertation.

Arlander, on the other hand, argues that artistic research is an acknowledged field of research and knowledge production, rather than a specific methodology. Artists undertaking research can use various methodologies

(Arlander 2013, 153). In many ways, Arlanders approach seems to sound true based on a review of a handful of practice-based PhD theses that I have come across. Each artist-researchers practice is different, and each artistic research process has different questions, tasks and objectives, and for this reason each must choose for themselves what type of process will best suit their particular inquiry. As a result, artistic research dissertations will invite at times an eclectic mix of methodologies most suitable for that particular research task.

Candy and Edmonds state that: a basic principle of practice-based research is that not only is practice embedded in the research process but research questions arise from the process of practice, the answers to which are directed toward enlightening and enhancing practice

(Candy & Edmonds 2018, 63). This is in part true by my experience, inasmuch as is concerned the components of my research in which I experiment with unconventional uses of the voice interface, or: repurposing the voice/interface, as I like to conceptualise it. In that aspect of my research, I study the ways in which people perceive the act of speaking to the computer (in the context of my works) in order to enhance my use of voice/interaction as a medium or artistic strategy.

Moreover, simply the process of experimenting with and exploring the use of voice / interaction allows me, as a practitioner, to build new knowledge about voice / interaction as an artistic strategy. I reflect verbally on my particular use of voice / interaction, and dwell on the rhetoric of the voice and of voice interaction in my works.

Another differentiating factor of presenting practice-based research is that a full understanding of the significance and context of the research can only be obtained by experience of the works created as distinguished from using them as illustrations

(Candy and Edmonds 2018, 65). This is in particular true for the works in this dissertation, which are process-based, digital and procedural interactive works. The works unfold in time in unique ways based on the way people interact with them. The experience of interactive art cannot be conveyed by images, nor by video documentation, since the crucial component, the experience of making a chain of choices, is impossible to portray through images or video.

☉

A further important contextualisation of my particular approach to artistic research is that my work is specifically interested in tackling philosophical, psychological, political and sociological issues related to the phenomenon of human migratory movement. My intention is to address these issues through language-based, time-based, interactive, browser-based art. My thinking is inspired by adjacent areas of research such as sociology and political science. I personally explore the issues as I think about how to represent dynamic relationships though code. But I also invite others to reflect on the topics through engaging with my work. My approach to artistic research can thus be considered transdisciplinary. Borgdorff articulates the specific contribution of artistic research in this type of context as such:

Much artistic research does not limit itself to an investigation into material aspects of art or an exploration of the creative process, but pretends to reach further in the transdisciplinary context. Experimental and interpretive research strategies thus transect one another here in an undertaking whose purpose is to articulate the connectedness of art to who we are and where we stand. Much of today’s visual and performing art is critically engaged with other life domains, such as gender, globalisation, identity, environment, or activism; philosophical or psychological issues might be addressed in artistic research projects as well.

(Borgdorff 2012, 166)

In this artistic research I take the approach that digital works can be utilised for imagining and playing with yet impossible realities, for asking questions, and for portraying aspects of life so that we may look at them from a distance and reflect on them. Each work is concerned with very different types of questions around migration, but overall and as a triptych the works ask what the movement brought about by migration implies from a human standpoint. The themes encompassed extend from perspectives of language, where movement results in accent which provokes a notion of the Other and a fear of the Other (We cannot take them all), the movement induced by the tension between personal needs and desires, but that is governed by (shifting) borders (Speak out) and at migratory movement as something which brings about homesickness but also a process of rooting in a new environment and a ambivalent relationship between the here and the there (Transplanted).

☉

My artistic practice is therefore the central force which drives this research process. I have created work in order to explore human migratory movement through different angles. In doing so, and in having to specify the rules of my computer programs and to think about how to tie in voice/interaction and my central themes, I have had to further reflect on my own understandings.

Throughout, I have conceptualised the migratory movement of our species as movement, and upon turning the metaphor into an interactive computer program which unfolds on the screen, I have had to further refine and simplify my ideas. I have shown my work to others and thought about what their interpretations and responses say about the work. I have formally interviewed people to obtain an even more detailed picture of how people are experiencing the work, responding to it and making sense of it.

☉

How then, do we evaluate artistic research? Borgdorff underscores the importance of assessing the research from the angle of the contribution that the artworks make in light of the issues they address:

The difference between artistic research and social or political science, critical theory, or cultural analysis lies in the central place which art practice occupies in both the research process and the research outcome. This makes research in the arts distinct from that in other academic disciplines engaging with the same issues. In assessing the research, it is important to keep in mind that the specific contribution it makes to our knowledge, understanding, insight, and experience lies in the ways these issues are articulated, expressed, and communicated through art.

(Borgdorff 2012, 166)

That is, for artistic research that takes place in an interdisciplinary context wherein the artistic practice tackles issues beyond art itself, Borgdorff is saying that evaluation of the artistic research needs to consider especially how these interdisciplinary issues are articulated, expressed and communicated through the art. I defend that all the works created are consistent in the sense that they address their respective themes in relevant ways, coming up with idiosyncratic ways to deal with the issues that they address.

It has not been obvious to me how to go about evaluating my research process and my research outputs. What are my research outputs? Are the artworks my research output? Or are the interview transcripts the outputs of my research? Is this dissertation (the written documentation of the artistic research process) the sole content which should be evaluated?

Borgdorff lists seven questions that can be used to assess an artwork or practice as research:

- It is indeed research?

- Does the research deliver or promise to deliver new insights,

forms, techniques, or experiences?- What knowledge, what understanding, and what experience is

being tapped, evoked, or conveyed by the research?- Is the description or exposition of the topic, issue, or question sufficiently lucid to make clear to the forum what the research

is about?- What relationship does the research have to the artistic or the social world, to theoretical discourse, and to the contributions that others are making or have made on this subject?

- Does this experiment, participation, interpretation, or analysis provide answers to the question posed and, by so doing, does it

contribute to what we know, understand, and experience?- Does the type and design of the documentation support the dissemination of the research in and outside academia?

(Borgdorff 2012, 212)

Borgdorffs proposed list of seven questions for evaluating artistic research can be thought of as complementary to other ways of evaluating research. One of the questions I have struggled with is whether I should be evaluating my work in the light of whether or not it magnates to successfully communicate my original intentions. As we will later on see with my evaluation of We cannot take them all, the work might in fact be communicating something quite different than what I intend, at least for some of the people who engage with it. But is this a problem? Or can the artwork be thought of as having some degree of agency, or freedom or room for interpretation, in the sense that it may be appropriate for the artist to cede control of its interpretation to those who engage with it?

☉

In the next section I will introduce the notion of (exploratory) programming as an artistic practice and as a method of inquiry itself.

1.2 Writing code as artistic practice

I conceive of my practice as exploratory programming (Montfort 2021), wherein the act of programming itself is what sometimes leads the way. That is, my artistic ideas are not necessarily fully defined to begin with, rather, some central notions guide me and only through the iterative, exploratory and at times even playful practice of composing code, do I arrive at my final results. The act of coding and trying out various kinds of ideas about processes as relationships helps me to think through my themes as well.

Moreover, I have always intuitively felt that the code I write, as a form of language and with its structures, function and variable names, as well as my comments, is as important as the experiences which it produces, and so in this sense the way I conceptualise my own programming practice and the code itself is informed by ideas circulating in the field of critical code studies that was initiated by Mark Marino in the early 2000s (Marino 2020; Marino 2006). Marino conceptualises the need to read code critically like this:

As code reaches more and more readers and as programming languages and methods continue to evolve, we need to develop methods to account for the way code accrues meaning and how readers and shifting contexts shape that meaning. We need to learn to understand not only the functioning of code but the way code signifies. We need to learn to read code critically.

(Marino 2020, 5)

Marinos critical approach to code, which looks at code and practices of coding amongst other through postcolonial and feminist lenses, has been very inspirational for me in that I have found my personal approach validated especially through Marinos naming of one of the toxic aspects of programming culture. Marino calls it encoded chauvinism, the:

denigrating expressions of superiority in matters concerning programming, which I see as a foundational element of the toxic climate in programming culture, a climate which often proves hostile—particularly to women and other minority groups—and is a kind of technological imperialism.

(Marino 2020, 134)

This encoded chauvinism may dictate for example that code should be as concise as possible in order to be considered elegant. I appreciate this type of concise coding, but I personally take an exactly opposite approach to coding. I call my coding style verbose, and I write it as close to prose as possible through function and variable names and frequent comments, in part for my own sake (so that I can also later make sense of what my code does), and in part so that especially novices that read it can make as much sense of it as possible through the long and expressive variable and function names such as goTowardsClosestAllowedZone(). Marinos inclusive and critical approach in critical code studies has been essential for feeling that my approach is also valid and important even if it may be out of line of the majority programming culture.

The ideas of critical code studies also inform my approach to presenting my work, because I not only describe what my code does, but also discuss selected snippets of the code itself. That being said, I acknowledge that my code can be read in a plethora of ways beyond my own reading, and look forward to critical perspectives that others may find in my code in the future.

I also want to discuss programming as artistic practice because I think that there are certain aspects of programming as practice which deserve to be highlighted to a reader that may not themselves be familiar with programming as a way of making things. Consider this idea:

Joseph Weizenbaum didn’t just design the first chatbot, Eliza, and then get someone else to do the programming later… These and dozens of other major breakthroughs were made by programmers who used programming to think, doing creative computing and programming as inquiry.

(Montfort 2020, 9)

What Montfort is saying here is that in the history of computer science, breakthrough ideas have to necessarily be worked on through programming itself. They are not created by someone sketching out an idea and another person implementing it, because so many important things happen in the actual process of making. Moreover, certain things can only be thought of by someone who has at least some idea of how programming works.

By my experience, it is this process of making or programming which slowly iterates and builds up to the final product

that will eventually become the explicit expression of the code, or the "work itself". But it has rarely been possible for me to arrive at this final product through a linear process, from specification through execution to final production. In fact, Montfort defines instrumental programming, as programming with the motive: to implement specifications and solve specific problems rather than using programming to explore

(Montfort 2020, 2). In this approach, I would sketch out an idea and then implement exactly what I had sketched out.

By contrast, Montfort suggests an approach called exploratory programming, where the purpose is to make use of programming’s facility for sketching, brainstorming, and inquiring about important topics

(Montfort 2020, 2). This approach is in line with my experience of programming as artistic practice, where the process of programming will be jagged and twisted and involve lots of avenues of trial and error, the implementation of aspects or functions that eventually come to be discarded etc. In total, the exploratory process itself is what builds my understanding of what it is that my work is actually about, what are its most important aspects and what are the directions that it should take. The notion of exploratory programming also allows me to play with different rules in my system and to see and experience how those rules change the meaning of my work.

Other concepts that are closely related to exploratory programming is the widely used notion of creative coding but also Winnie Soon & Christoph Coxs’ aesthetic programming which is strongly rooted in the idea that programming as a practice and software works themselves are a means to engage in a critique of our social contexts (Soon & Cox 2020). Aesthetic programming departs from the notion of political aesthetics:

Political aesthetics refers back to the critical theory of the Frankfurt School, particularly to the ideas of Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin, that enforce the concept that cultural production — which would now naturally include programming — must be seen in a social context. Understood in this way programming becomes a kind of

force-fieldwith which to understand material conditions and social contradictions.(Soon & Cox 2020, 15)

Like Montforts notion of exploratory programming, aesthetic programming places an importance on skill, on understanding and practicing programming as a means to deeply understand the systems in which software is rooted:

Aesthetic programming in this sense is considered as a practice to build things, and make worlds, but also produce immanent critique drawing upon computer science, art, and cultural theory. From another direction, this comes close to Philip Agre’s notion of

critical technical practice,with its bringing together of formal technical logic and discursive cultural meaning. In other words, this approach necessitates a practical understanding and knowledge of programming to underpin critical understanding of techno-cultural systems, grounded on levels of expertise in both fields… Such practicalknowingalso points to the practice ofdoing thinking,embracing a plurality of ways of working with programming to explore the set of relations between writing, coding and thinking to imagine, create and proposealternatives.(Soon & Cox 2020, 15 - 16)

Much like Montforts invitation of non-programmers

to embrace programming as a means to explore issues encompassing diverse areas of human existence, so aesthetic programming also invites a queering of the traditional divide between programmers and non-programmers to encourage a wider group of people to engage with the practice of coding:

By engaging with aesthetic programming in these ways, we aim to further

queerthe intersections of critical and technical practices … and to further discuss power relations that are relatively under-acknowledged in technical subjects. We hope to encourage more and more people to defy the separation of fields and practices in this way.(Soon & Cox 2020, 16)

I struggled at the outset of my PhD research with feeling like I would not be capable of programming well enough to use programming as a way to explore the issues that felt important to me. By the time I began my PhD, I only had a meagre 6 months of practical programming experience in javascript and HTML, so I felt as though I could not possibly pursue a practice of programming and its related artistic strategies. But the pull towards thinking in procedures and of making work where there was a role designed for users/interactors/participants/players/etc. was so strong that I resolved to overcome my fears and sense of not being capable of programming, because I very strongly felt that I wanted to explore these specific ways of creating and making. I was feeling especially intrigued by voice/interaction, and I knew that it would be possible to explore these artistic strategies if I made an effort to learn more about programming.

In this sense programming is just a one more tool or a material for implementing ideas, a process of engaging in a specific kind of activity in order to work through and on ideas. Nöe argues that artistic activity is always related with some form of craftsmanship:

To understand art, I propose, we need to look at it against the background of technology. Artists make stuff, after all: pictures, sculptures, performances, songs. And art has always been bound up with manufacture and craft, with tinkering and artifice.

(Nöe 2015)

In the same way that a sculptor is one who conceives of their idea and then executes it with their knowledge of the material in a process of manufacture and craft, as Nöe suggest, so my understanding of my own practice as an artist (that uses programming) implies engaging with the actual act and craft of programming. The act of using my tools and my material to create my work.

☉

First and foremost my process of exploratory programming is characterised by the pauses I need to take in order to ponder about the choices I make in my code. A crucial part of this is to realise my ideas so that I may see and experience them in their procedural form.

What are the implications of working by programming from the perspective of artistic research? Possibly the most important aspect is that code can easily be modified. Hence, I can declare my work finished only to modify it a moment later. Each time I modify one of the procedural aspects of my code, the meanings within the work will change, as we will clearly see in the following chapters as I discuss the work in more detail.

This means that programming, as artistic research, is dialogical. Once my ideas are embodied in the code, the code becomes a procedural system which expresses my ideas through language, through audio, through the visual and importantly, through different kinds of processes. In a way, the code is just the bones and when it compiles on my browser, what I see and hear and the processes which I experience are like my ideas in flesh. Seeing the form which my code takes on screen allows me to observe, to ponder and to reflect on my own ideas. Only once I see my ideas come to life on the screen am I able to understand where to take my work next. The process is thus naturally iterative.

Throughout the course of my iterative programming practice, I have pursued different kinds of trajectories which have not proven successful and I have had to take steps backwards and sideways to rethink my ideas completely. While the core idea of each of the works has always remained the same, much of the details of how I have implemented the ideas have changed along the way.

Additionally to my private and personal iterative and reflective exploratory programming practice, the input of others, both in informal and formal contexts of evaluation, have been crucial in allowing me to understand what my work is about and to make the work better able to express the ideas. In fact, each encounter with another person through my work has pushed the work forward and onto another cycle of iteration. I will speak in more detail about this in the next sections, and justify why I chose to engage in formal user research through video-cued recall and interviews.

☉

In the next section I will introduce the notion of a procedural system and explain how procedural systems can allow for play, two of the central notions which are responsible for creating meaning in my work.

1.3 Procedural systems and experience through play

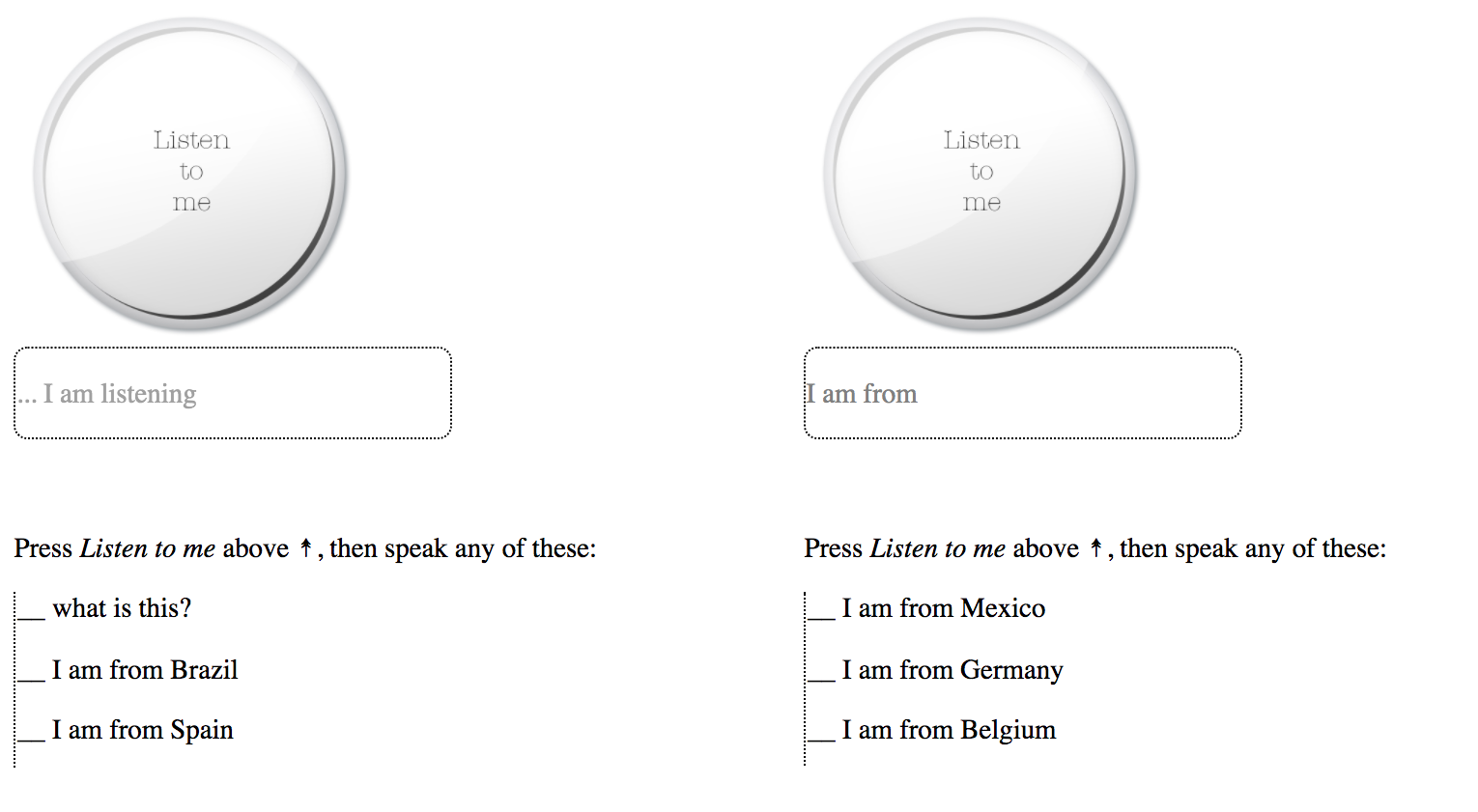

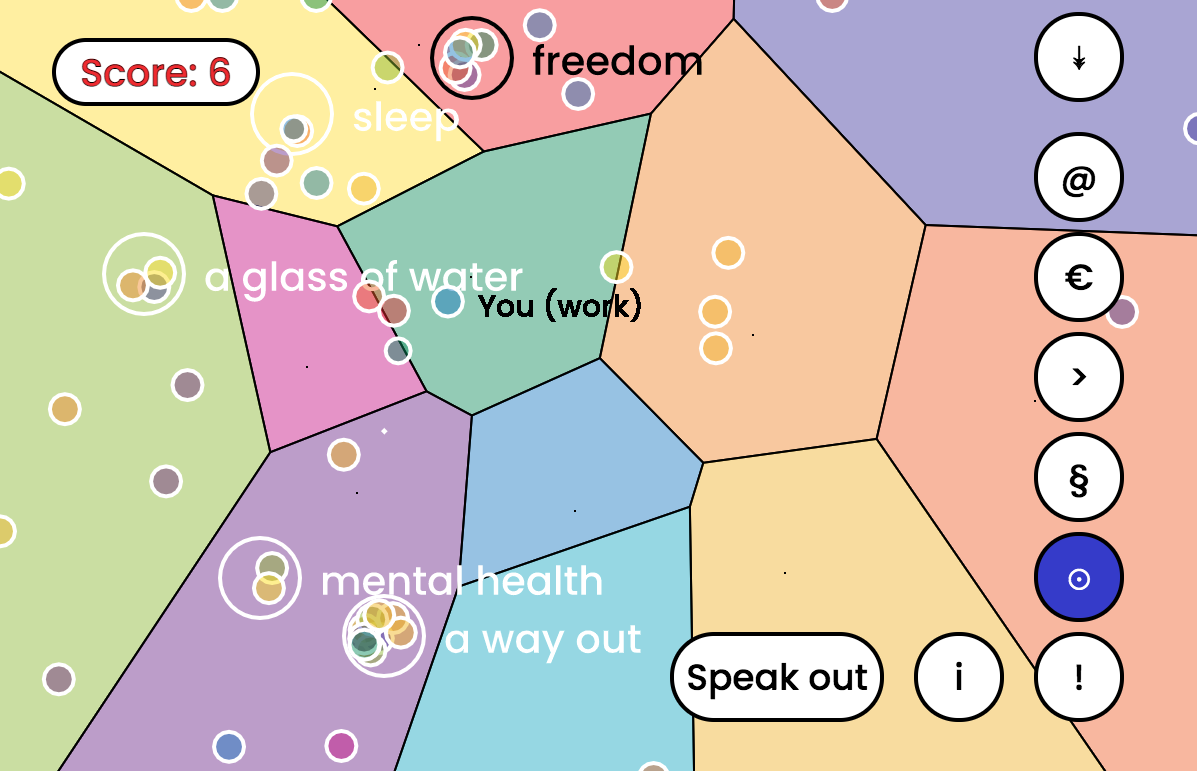

My main material or tool is programming. As an artist, I am a programmer like someone else might be an illustrator or a poet. I am most concerned with expression through creating procedural representations of some aspects of the world which I am interested in addressing, and in portraying these aspects predominantly through language and concepts. I call upon the person engaging with my works to interact with them to discover the themes they address. In the case of Speak out, I have implemented some simple game mechanics in order to build a space for play as a means of interaction.

Let me clarify what I mean by procedural representations and what is the role of play in exploring and making sense of my work. Murray observed in 1997 that computer programs are intrinsically procedural: to be a computer scientist is to think in terms of algorithms and heuristics, that is, to be constantly identifying the exact or general rules of behavior that describe any process

(Murray 1997/2016, 73). In other words, to program means that we must think about how it is that we can represent some process through code.

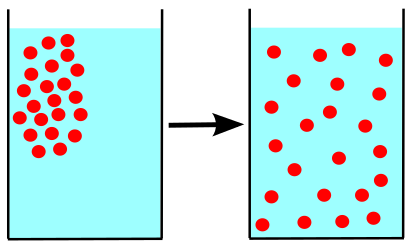

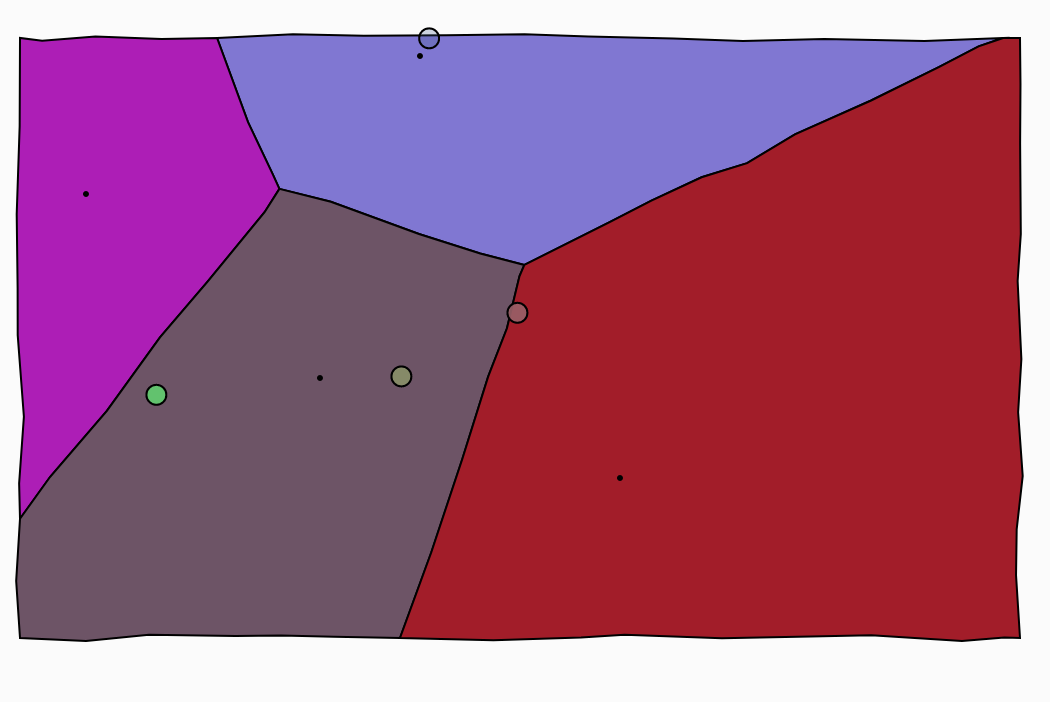

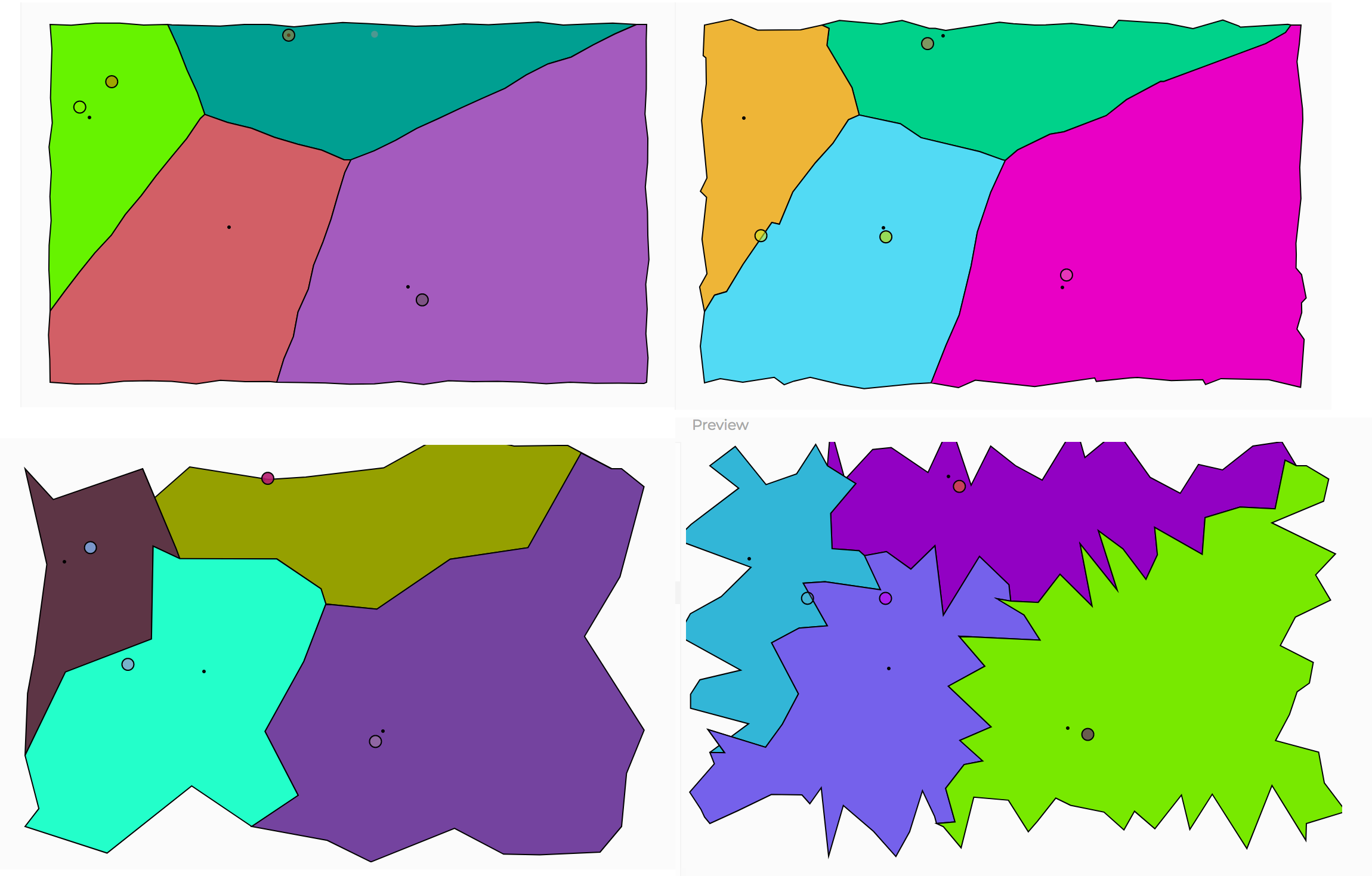

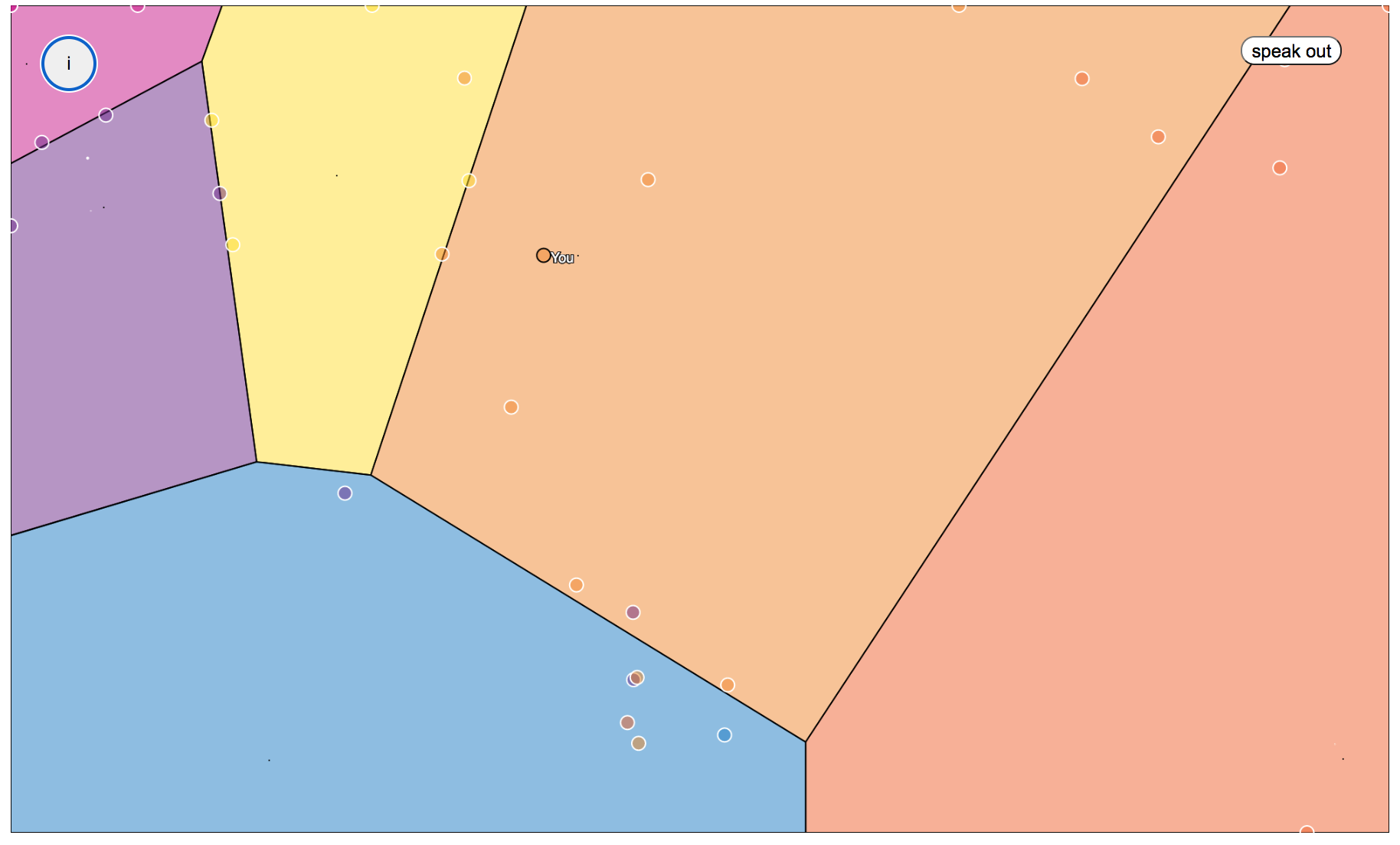

For example, in Speak out, I modelled the behavior of some small randomly emerging particles such that they are free to roam around randomly on the screen. However, if they find themselves in a zone where they are not allowed to be, they will begin to bump against the limits of that zone. In order to produce this type of behavior, I had to write some code that would check whether the particle is in an allowed zone, if yes: move randomly, if not: go towards a zone where they are allowed to be. This constant checking in the code produces, visually, the behavior which I desired. At the same time, I am modelling an aspect of the natural world, spaces, both tangible and intangible, delimited by borders, which limit the movement of human beings.

Murray describes another very important aspect of a procedural system as opposed to a static animation: